Four Rediscovered Plants

Emily Ellis

Plants have a way of surprising us. Scientists frequently stumble across “extinct” species in remote jungles and on lonely mountain sides, and while stories of these rediscovered plants often skirt under the headlines, they highlight how much there remains to learn about these incredible organisms - and the importance of preserving their habitats, so they don’t vanish before we can find them.

Even some of our most recognizable plants have puzzled botanists. Take the lilac, for instance: a lovely, fragrant ornamental plant now found in gardens throughout the world. The lilac was popular in Europe following its introduction to Italian and Austrian gardens in the Renaissance era, but its native habitat was unknown, and would remain so - at least, to scientists - for centuries. When the plant was spotted growing in 1794 in modern Bulgaria, researchers had to reconsider all they thought they knew about the plant.

The rediscovery of the lilac is just one of many tales of lost and found plants. To celebrate our upcoming “Treasures of the Oak Spring Garden Library” lecture on the discovery and rediscovery of the lilac and the horse chestnut (there are still tickets available!), we’re sharing several incredible recent stories about rediscovered plants. Scroll down to read more.

Coffea stenophylla

Ji-Elle via Wikimedia Commons

Climate change is a daunting reality that will affect (and has affected) many of our most important plant species, including the ones we eat. Coffea arabica, the world’s most widely grown and consumed coffee species, is one crop species at threatened by rising temperatures - an impeding loss not only for those of us with caffeine addictions, but for the people who depend on the plant for their livelihoods. For this reason, scientists were thrilled when they “rediscovered” Coffea stenophylla in the forests of Sierra Leone in 2020: a wild coffee species that is heat and drought-tolerant, with a similar flavor to Coffea arabica.

Stenophylla was farmed and exported to Europe until the early 20th century, when it was replaced by the more popular Coffea Robusta. In the following decades, the plant seemingly vanished; while a couple specimens existed in research collections, the last plant spotted in the wild was seen on the Ivory Coast in the 1980s, and it was believed that deforestation had driven the plant to extinction. The rediscovery of this drought and disease-resistant plant offers hope for the future of coffee growers, sellers, and consumers everywhere.

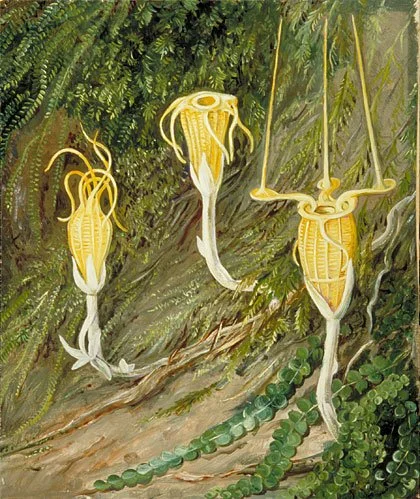

Thismia neptunis

Marianne North, Singular Plants of the Dark Forests of Singapore and Borneo, 1869. https://www.kew.org/mng/gallery/244.html

This wonderfully bizarre plant many look like something you’d see growing in the background of a SciFi film, but it’s actually a mysterious parasitic flower that eluded scientists for 150 years before it was photographed in Malaysia in 2018.

Part of Thismia neptunis’ mystique is the fact that it spends most of its life underground, making it quite hard to spot. It is a mycoheterotroph - a type of plant that it derives nutrients from fungus in the soil that is attached to nearby photosynthesizing plants, instead of using photosynthesis itself - and only sends up a stalk when it is time to flower, usually for a few weeks out of the year.

There is much scientists have to learn about this plant - including, how it is pollinated - but they may have a while to wait: according to this article from The Smithsonian, it hasn’t been spotted again since.

Velvet Pitcher Plant (Nepenthes mollis)

Photo: Re:wild.org

For a hundred years, the stunning velvet pitcher plant - named for its coating of brown hairs or trichomes, which, in pitcher plants, are typically used to repel water - was only known to scientists by dried specimens that were collected in Indonesia in 1918. In 2019, Global Wildlife Conservation (now Re:Wild) announced that a team of independent botanists had found the plant in the dense wilderness of Borneo. While much remains to be learned about the Nepenthes mollis such as whether its range is limited only to Borneo or if it is found in other locations, its rediscovery was an exciting find for Re:Wild’s Search for Lost Species Project.

Jimmy Red Corn

Photo by Caitlin Etherton

This “lost” crop is particularly special to us here at the Oak Spring Garden Foundation. Jimmy Red, a ruby-colored Appalachian dent corn, sprouts in the Biocultural Conservation Farm’s seed-saving plot, and every year we bring the corn to a local mill to be ground into grits and cornmeal.

While you can purchase Jimmy Red corn today, that wasn’t the case until around a decade ago. In earlier centuries, Jimmy Red corn - which was likely first cultivated by Native Americans in the southeast, although by which Tribe is unknown - enjoyed a reputation a particularly tasty hooch crop. Named for James Island in South Carolina, it was used to make moonshine in Appalachia and other parts of the south before it began to disappear from plots in the late 20th century.

After one of the last known bootleggers in South Carolina passed away, two surviving ears of the corn were rescued from his garden and brought to farmer and seed saver Ted Chewning. Along with other growers and chefs, Chewning helped bring the crop back from the brink of extinction in the early 2000s. Since then, Jimmy Red has made a comeback and is celebrated by farmers, foodies and chefs far and wide.

Want to visit the beautiful Oak Spring Garden Library and learn about a couple more of history’s rediscovered plants? Sign up for upcoming lecture, “The Discovery and Rediscovery of the Horse Chestnut and the Lilac: New Science from Old Books.” Led by Professor Hans Walter Lack, former Director of the Botanical Garden and Botanical Museum in Berlin, guests will be able to examine a copy of Mattioli's Commentarii from the mid-1500's, which contains the first printed illustrations of both plants, as well as visit the Mellon Main Residence for coffee and conversation. Get your tickets here.

Banner image: Jean-Louis Prevost, Collection des fleurs et des fruits. Paris, c. 1745-c. 1810