Wondrous Weeds

Emily Ellis

We pass them on roadsides without notice, crush them beneath our feet as we stroll across our lawns, and yank them out of our gardens as if they’d done us personal harm. Yet some of the world’s most ubiquitous and pervasive weeds have storied pasts and incredible healing properties, rooted in our histories as firmly as they’re rooted in our backyards.

In the introduction to An Oak Spring Herbaria (Lucia Tongiorgi Tomasi and Tony Willis, 2009), Bunny Mellon noted that an herb, according to The Standard Cyclopedia of Horticulture, could be defined as any plant that “dies to the ground each year, or at least does not become woody.” She then went on to list five herbs, which most of us would classify as weeds, that grow abundantly around the Oak Spring Garden Library in the warmer months and have been used for thousands of years as medicine.

In celebration of National Herb Week, we’re featuring these five plants - favorites of Mrs. Mellon, as well as many other people throughout history who have enjoyed their medicinal and culinary benefits. If you want to learn more about the rare herbals in the Oak Spring Garden Library, which contain beautiful illustrations of these plants and other herbs, you can read the digital catalogue for free at issuu.com or purchase a hard copy from our library page.

Mullein

A young mullein growing outside the Oak Spring Garden Library.

Furry, towering mullein is a common sight sprouting between the paving stones at Oak Spring, both in and around the formal garden and the library. Mrs. Mellon was fond of the herb from a design perspective, describing it as “a most majestic plant” in the introduction to An Oak Spring Herbaria. Its presence is one of the many little details that make the site so special.

However, it also has a long history as a medicinal herb. An oil made from the flowers of the plant, thought to have strong antiseptic and anti-inflammatory properties, has been used for centuries to treat earaches in children; a study published in The Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine in 2001 concluded that this treatment was as effective as an anesthetic one. Native to Europe, North Africa, and Asia, mullein likely arrived in North America in the pockets of British Puritans, who would have considered it an essential addition to medicinal herb gardens. Aside from treating earaches, tea made from the stewed leaves and flowers has long been a treatment from respiratory illnesses, helping to expel mucus and soothe irritation. It has also been smoked as a tobacco substitute.

Commissioned by Mrs. Mellon from Margaret Stones, 1986.

Although not very palatable (it’s a bit too fuzzy to add to a salad!) people have found plenty of other uses for the versatile herb. Historically, seeds of the plant were used to poison fish throughout Asia and Europe by fisherman looking to make things a little easier on themselves; the King of Germany even outlawed such practices as early as 1212 AD. Another interesting use for the plant was as a light; as Mrs. Mellon noted, the stalk “when dipped in suet will burn like a candle.”

Mullein is usually found in sunny areas where the soil has been disturbed. Most types are perennials, returning year after year. The seeds remain viable for many years in the soil (archaeologists have found viable seeds in soil samples dated from A.D. 1300!), so it’s a very hardy herb - one of the reasons why it flourishes on Oak Spring’s many stone patios.

Pokeweed

Pokeweed lining a path beside one of Oak Spring’s restored meadows.

Common, gangling pokeweed, with its deep purple, poisonous berries, often falls victim to the weed-whacker. However, this native North American herb is arguably one of the world’s most fascinating medicinal plants, containing a particular antiviral protein that researchers believe could be used in the treatment of cancer, herpes, and HIV. Indigenous people in North America were using pokeweed as medicine and food long before major universities began publishing papers about it, using the herb both in teas and poultices to treat cancers, arthritis, scabies, and neurological disorders.

In addition to its uses as medicine and as a dye plant (its name comes from an Algonquin word, “puccoon”, meaning “plant with dye”), parts of pokeweed are a nutritious spring side dish - if prepared properly. Particularly in poorer communities in Appalachia and elsewhere in the south, the nutritious young shoots and leaves were either pickled or prepared in “poke sallets”: boiled several times in clean water to remove toxins, then fried in bacon drippings and seasoned with salt, pepper, and molasses. The greens are high in Vitamin A and C, helping folks earlier decades get through the relatively sparse early spring.

Bigelow, Jacob, 1786-1879. American Medical Botany.

Ready to start digging into that pokeweed taking over your backyard? Not so fast: because the plant is quite toxic - particularly to children and older people - it’s not a good idea to eat it unless you are experienced with its preparation. If you live in the south, you might want to check out one of the region’s annual Poke Sallet Festivals to learn more about this fascinating herb.

Dandelions

By Sophie Grandval, 1990

Widely considered a weed today, the humble dandelion is one of history’s most ancient medicinal herbs. Likely native to Europe and Asia, the seeds of this plant were carried around by humans before written history to plant for food and medicinal purposes. Like mullein, they were brought to North America in the 1700s by British puritans, and, as you have probably noticed, have flourished here ever since. Unlike many plants, all parts of the dandelion are edible (although you probably don’t want to take a bite out of the fluffy seed pods); the leaves are nutrient rich and great in salads, the roots can be roasted, fried, or dried and ground for a coffee-like drink, and the blossoms can be steeped into a tea or made into wine. Theseus turned to dandelion salad for a pick-me-up after battling the Minotaur, so you know it would make a good spring side dish - just make sure to forage from pesticide-free areas!

Dandelions growing in a field on Rokeby. Photo by Caitlin Etherton.

Like many medicinal herbs, dandelion has been used to treat a variety of ailments around the world for centuries. Today, it’s most commonly used as a diuretic and to promote liver and digestive health. It is also a favorite of important pollinating insects like bees - all the more reason, as Mrs. Mellon wrote, to allow your fields to be covered in “its bold yellow flowers.”

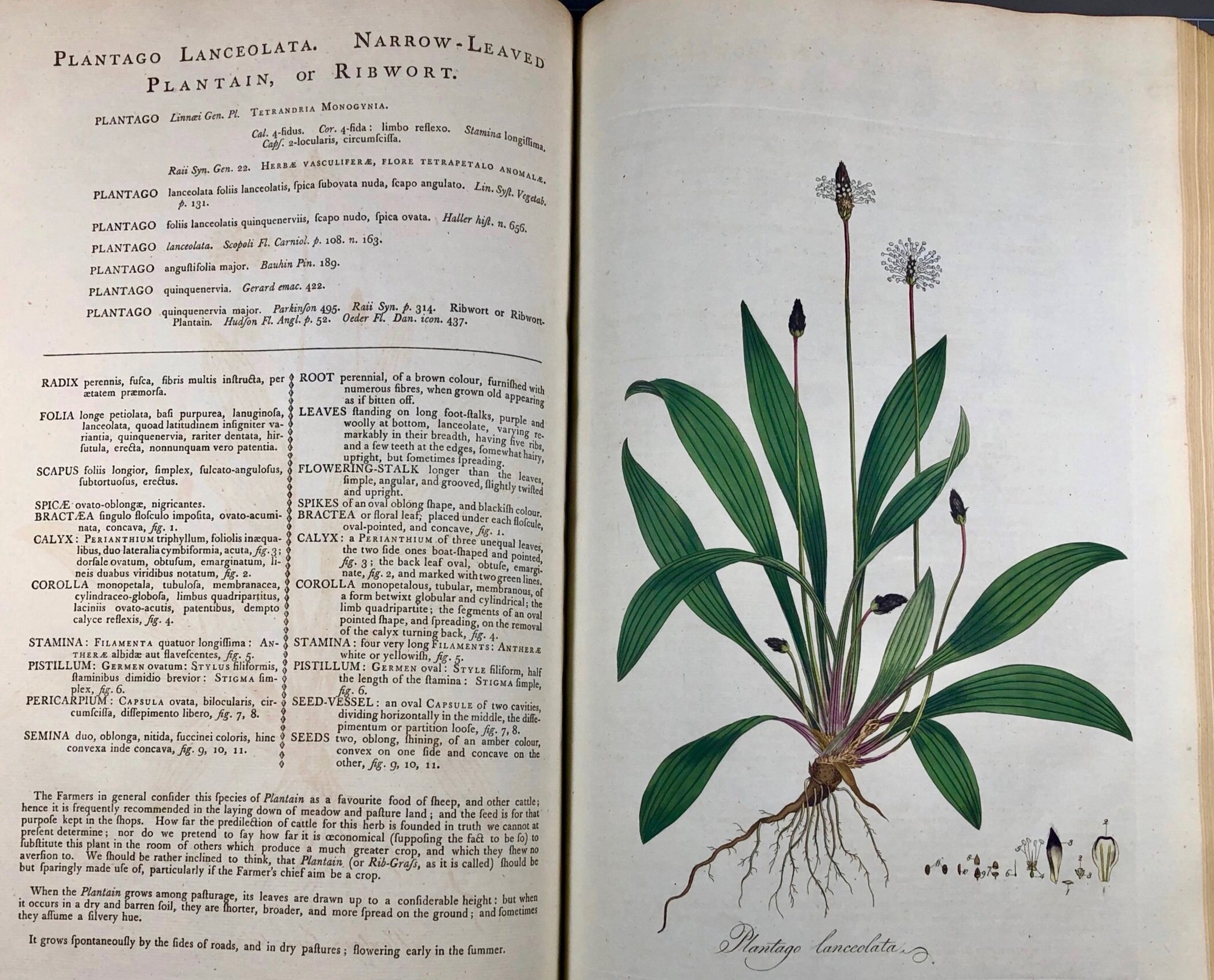

Plantain

Have you ever shot the pop-offable seedheads of plantain at your friends? Or wadded up leaves to slap onto a bee sting? This pervasive herb is easy to spot in backyards, playgrounds, parking lots, and has been helping to heal sore and itchy skin for thousands of years.

Like mullein and dandelion, plantain is native to Eurasia and was likely brought to North America as a culinary and medicinal herb. It has been used in traditional Iranian, Arabic, Greek, Chinese and Indian medicine since ancient times; Persian medical texts dating back to the 10th century describe it as being used to treat skin problems, wounds, neurological issues, pulmonary and digestive complaints.

Plantain growing outside Oak Spring’s Loughborough Barn.

While the medicinal properties of plantain are still being studied, one thing we do know for sure is that it definitely helps with bee stings: make a simple “spit poultice” for your sting (unless you’re allergic; in that case, seek medical attention!) and its astringent and anti-inflammatory properties will immediately soothe the pain and itch.

Yarrow

Doart, Denis. Memoires pour servivr a histoire des plantes. 1676

The Linnean name for the group of flowering plants known as yarrow, Achillea, comes from Greek legend, when the warrior Achilles used the herb to stop the bleeding wounds of his soldiers during the Trojan War. This common plant, native to Europe, Asia, and North America, has played a role in traditional medicine ever since (and likely before!) throughout its range. There are both native and introduced species in North America; in Virginia, it’s a common sight in fields and roadsides during the warmer months.

Besides its well-earned reputation as a slower of bleeding (it’s also known as the nosebleed plant), yarrow has been used to aid digestion, treat anxiety, and treat skin complaints such as hemorrhoids- likely due to its anti-inflammatory properties. The young greens are also edible - try mixing them in a salad, or steeping the dried or fresh flowers in a tea.

Thanks to Biocultural Conservation Farm manager Christine Harris and head librarian Tony Willis for their help with this blogpost!