Jane Eleanor Datcher, Pioneering Botanist and Educator

Emily Ellis

Without great teachers to support and inspire them in their formative years, many of history’s most renowned scientists would never have made it past the drawing board. On this International Day of Women and Girls in Science, we’re celebrating by telling the story of botanist and educator Jane “Nellie” Eleanor Datcher. In addition to becoming the first Black woman to earn an advanced degree from Cornell University in 1890, she shared her love of plants and science with countless students over her four decades as a chemistry teacher at Washington D.C.’s historic Dunbar High School, the first high school to serve African Americans in the United States.

Jane “Nellie” Eleanor Datcher. Image from blogs.cornell.edu, via the Moorland-Springarn Research Center at Howard University

Datcher was born in 1868 in Washington, D.C. to Samuel and Mary Victoria Cook Datcher. She was part of a long line of prominent Black educators and community leaders in the District. Her maternal grandfather, Rev. John Francis Cook, Sr., was born into slavery in the Washington, D.C. area. He gained freedom after his aunt, Alethia Tanner – a well-known community leader in D.C. – earned enough money by growing and selling vegetables while enslaved to purchase her own freedom, and then later, that of Cook, his mother Laurena, and many other relatives and acquaintances. Reverend Cook would go on to found the 15th Street Presbyterian Church, becoming the first Black Presbyterian minister in the city.

While little is known about Datcher’s early life, it can be assumed that education was an important part of it. Datcher attended private and public schools for Black youth in D.C. before she and her cousin, Charles Chauveu Cook, enrolled in Cornell University when she was 19. Cornell would accept any person that could pass its admission requirements, making it one of the few institutions of higher learning that would admit Black students and Black female students at the turn of the 20th century. Despite the language in its charter, the school was not especially welcoming to people of color, and Datcher likely experienced racism as a student. An exhibit on Cornell’s Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections recounts incidents during the early 1900s in which Black female students were barred from residential dormitories, and were petitioned to be barred by white classmates.

Dame Ann Hamilton. Drawings of Plants. 1752-1766

Despite the challenges she faced, Datcher excelled at Cornell. She joined the botany department, where she studied two species in the hepatica genus (sometimes called liverleaf or spring beauty), a group of beautiful native wildflowers in the buttercup family. It’s possible that Datcher first encountered the flowers growing in the woodlands near her hometown in Washington, D.C. or as a student in Ithaca, as the flower can be spotted blooming alongside the city’s beautiful nearby Six Mile Creek. The leaves of hepatica are evergreen and their blossoms include shades of pink, blue, and white. They are among the first flowers to brighten the woods towards the end of winter, and it’s easy to imagine them catching a young botanist’s attention on an early spring day.

Image from blogs.cornell.edu, via the Moorland-Springarn Research Center at Howard University

Datcher’s hand-written thesis, titled "A biological sketch of Hepatica triloba Chaix and Hepatica acutiloba DC", led her to receive her Bachelor’s of Science from the Cornell Botany Department. She graduated alongside her cousin, Charles - who would go on to be an English professor at Howard University - and law student George Washington Fields. Together, the three were the first Black students to graduate from Cornell. In the 1890 graduation photo, Datcher’s position in the front of the class indicates her excellent academic standing.

After graduating from Cornell, Datcher brought her scientific knowledge to Howard University in her hometown, where she attended medical school from 1893-1894. She then took a position as a chemistry teacher at Dunbar High School (formerly the Preparatory High School for Colored Youth). She held the position until shortly before her death in 1934.

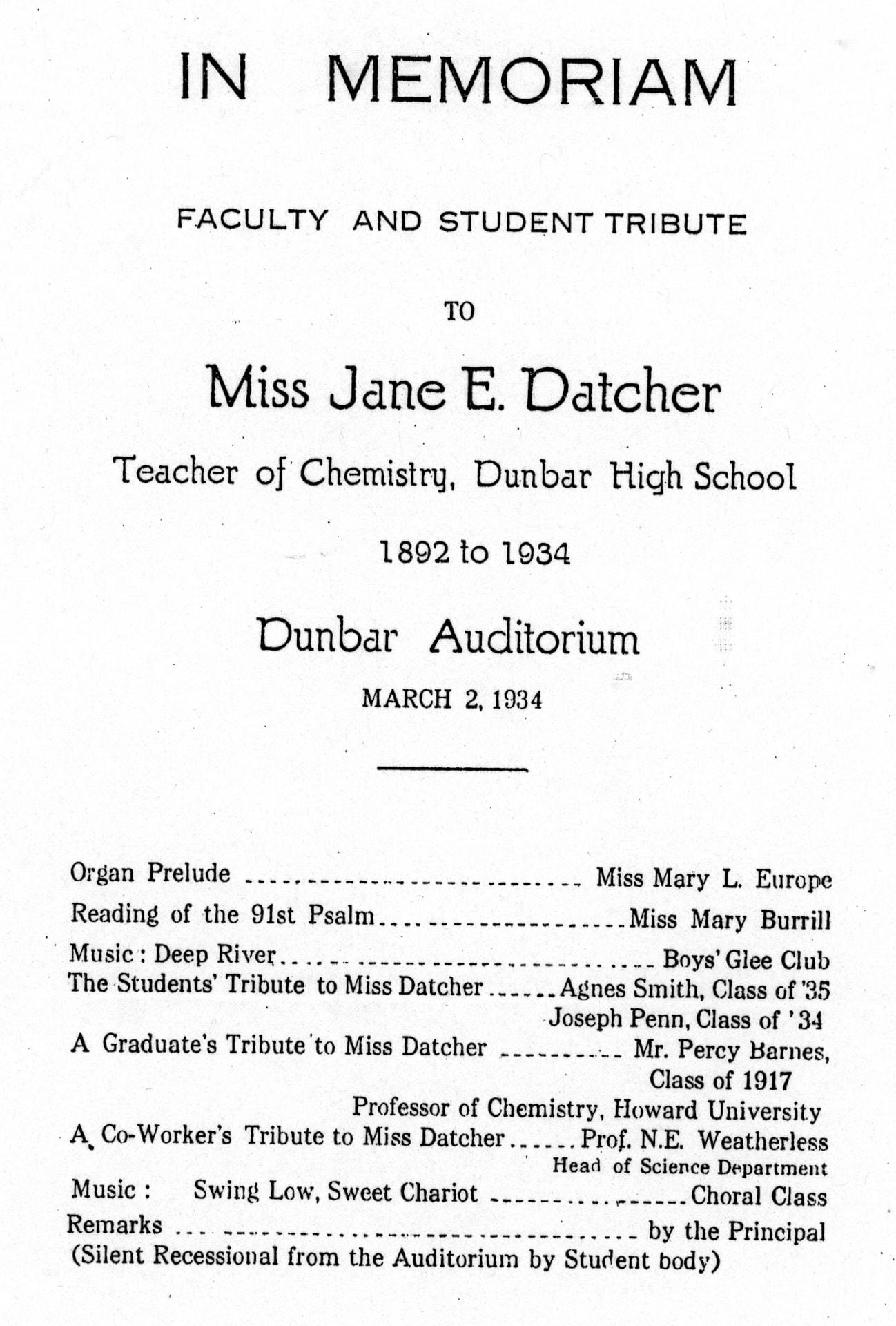

Although we don’t know the cause of Datcher’s death, we do know that she was mourned by her students and fellow teachers. At her memorial service at Dunbar High School in March of 1934, speakers included her former student Percy Barnes, a Howard University professor who was the first Black man to earn a Ph.D in chemistry degree from Harvard. Barnes was one of many notable graduates of Dunbar who went on to excel in STEM fields.

So little is known about Datcher’s life that it is difficult to describe the impact she likely had on the people who knew her, but from the loving tributes her students and coworkers gave after her death, it’s clear that she inspired many.

Want to learn about more historical women botanical pioneers? Read last year’s IDWGS blogpost about chemist Alice Ball. To learn about some of history’s other great female plant scientists, check out our Google Arts and Culture Exhibit, “The People and Plants Shaping Modern Medicine.”

Banner image: North American wildflowers, Washington, D.C., Smithsonian Institution, 1925