The Science Behind Evergreens

OSGF

Yuletide abounds with celebrations and decorations for the season. Whether they are bundled in a wreath on our door or standing out amongst the dormant landscape, evergreens are the shining stars of winter. Species like pines, fir, spruce, and holly are common staples this time of year and represent the promise that spring and the green it brings will return again. Read below to learn about how some of our common holiday greenery came to be and learn about the science behind how some of these plants remain evergreen.

Evergreen Origins

Fossils of Earth’s earliest land plants are dated back some 450 million years ago, with more recent research suggesting plants first made landfall some 500 million years ago, during the Cambrian Period. At this time the atmospheric oxygen levels on our forming Earth finally reached a point where living organisms once relegated to the water could survive on land. When these early plants made the transition from aquatic to terrestrial, they began developing modifications for their reproductive organs to not dry out in the new environment. The first iteration of this process was moss, which lacks any vascular tissue in the cells. Another iteration of early land plants were ferns and club mosses that reproduce through spores and contain vascular tissue, which gives plants their structure and helps them build height. Around the Devonian Period (419.2- 358.9 MYA) Earth saw the development of spermatophytes. This is the largest group of early seed bearing plants and includes both angiosperms and gymnosperms, the later of which hosts the iconic conifers associated with the winter season.

The word gymnosperms has its origins in Greek, meaning “naked seeds”. Instead of the seeds being enclosed in a fruit like that of angiosperms, a gymnosperm’s seed (or ovule) is exposed but it’s not visible to the naked eye. This is also the case for conifers whose small seeds are exposed on cones or modified leaves. Also included in the gymnosperm group are cycads, gnetales, and the ginkgo which have been covered extensively by OSGF President, Sir Peter Crane.

The common greenery that decks our halls and boughs falls into the subclassification of gymnosperms, conifers. The literal Latin translation of the word conifer comes from Latin meaning “cone-bearing”. It’s believed that cones were first derived from exposed seed which was staggered on widely-spaced branches. Eventually these branches and the other plant material on them developed and fused together over time so that each individual cone is made up of what was once an entire branch. Today conifer species have both male and female reproductive material on the same tree, making them monoecious plants.

Spruce and Fir

Beyond the pine cones, there are two common conifers which find their way into popularity this time of year for their lasting quality and fragrant foliage: spruce (Picea sp.) and fir (Abies sp.). Taking another look back into geologic time, both species regenerated in the boreal regions of the globe following the receding of glacier ice sheets back north some 20,000 years ago.

Since snow and ice are all too common in these areas, spruce and fir trees, along with many other conifer species, developed ways to stave off the cold. One of these adaptations is presented in their overall habit. Typical spruce and fir trees have a conical shape, which makes them a clear choice for a Christmas tree and means they’re less likely to retain heavy layers of snow. Shedding of snow or ice is also facilitated by the needles which have a thick, waxy coating that helps the trees retain water during winter and periods of drought. Their overall thin size helps too.

Despite these adaptations, it’s not without drawbacks. When evergreens carry their leaves they also carry with them any pathogens or diseases which can’t easily be shed like their deciduous tree counterparts. Lastly there is such a thing as too much snow, which can lead to damage of conifer branches but can be mitigated by shaking off the limbs of trees you’d like to protect if the snow layer is unusually heavy.

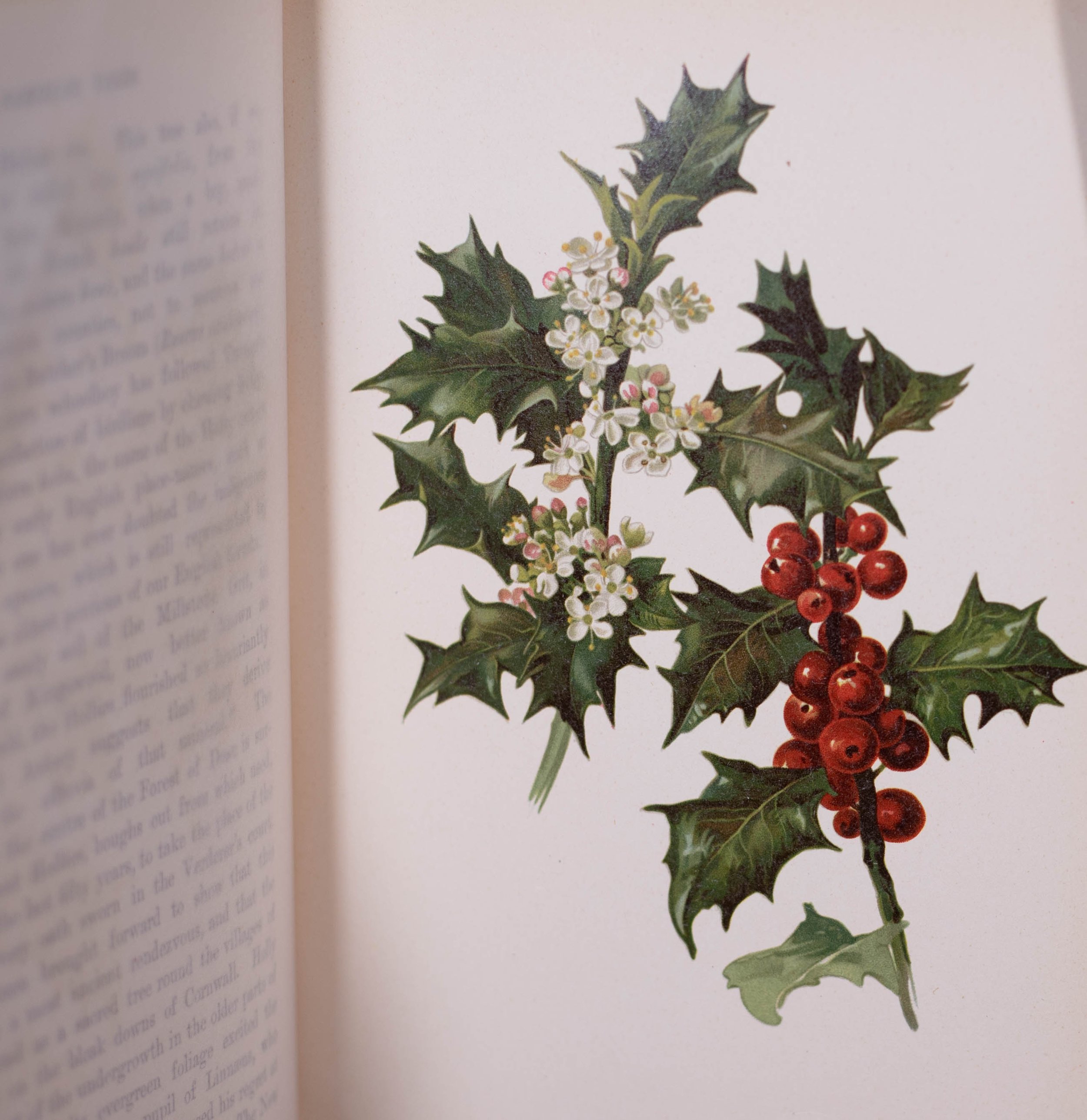

Hollies

Unlike the spruces and firs, hollies belong to the angiosperm clade of plants. The bright red berries we all associate with them are only produced under certain circumstances, regardless of whether they are deciduous or evergreen. Dioecious plants like hollies have male and female flowers on separate trees which means that in order for fruit set to occur, female trees have to be in proximity or otherwise pollinated by compatible male trees of the same or a closely related species. The flowers themselves are discreet with a white or yellow-ish color and a slight fragrance. Despite their less than flashy appearance for us humans, they’re attractive to pollinators when in flower during late spring.

Hollies have a worldwide distribution with at least one species native to every continent except Antarctica. The common European holly, Ilex aquifolium, is perhaps what most people picture in their minds when thinking of a holly and the one that’s most depicted in holiday stories, art and songs this time of year. A close second is the deciduous North American native, Ilex verticillata.

Winterberry in December (Ilex verticillata).

Winterberry is one of 17 other holly species native to eastern North America. Most are native to the lower southern states of Georgia and Florida. Some of the more popular uses this time of year for humans utilize the leaf-less twigs which have clusters of bright or sometimes orange berries. Birds also get enjoyment from them as they provide a good food source during a time when meals can become scarce.

References:

Anderson, Dave. “When Winter Snow and Ice Return to the Forest...” Forest Society, Society for the Protection of New Hampshire Forests , 9 Dec. 2019, forestsociety.org/forest-journal-column/when-winter-snow-and-ice-return-forest.

Conway, Stephanie. “Beyond Pine Cones: An Introduction to Gymnosperms.” Arnoldia, vol. 70, no. 4, 2013, pp. 2–14. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/42955548.

Crick, Julie. “Trees Avoid Damage from Freezing Temperatures: Part 1.” MSU Extension, 21 Jan. 2022, www.canr.msu.edu/news/trees_avoid_damage_from_freezing_temperatures_part_1.

McCourt, Shawn. Botanical Spotlight: Holly - December, Marie Selby Botanical Gardens, 25 May 2022, selby.org/botanical-spotlight-holly/.

Paulus, Kristine. “All Eyes on Ilex: Highlights from the Holly Collection " New York Botanical Garden.” New York Botanical Garden, 22 Jan. 2021, www.nybg.org/planttalk/all-eyes-on-ilex-highlights-from-the-holly-collection/.

“Reproductive Development and Structure - CUNY.” Reproductive Development and Structure, CUNY OpenEd, opened.cuny.edu/courseware/lesson/772/student/?section=3.

“UVM Tree Profiles : White Spruce.” Omeka, Center for Teaching and Learning at the University of Vermont, libraryexhibits.uvm.edu/omeka/exhibits/show/uvmtrees/white-spruce-introduction/white-spruce-natural-history.