Gardens of the Past

OSGF

A modest vegetable plot, the expansive grandeur of a palace lawn, the lure of a small winding path, gardens and their elements inspire something within us. These areas, whether precisely manicured or maintained with a gentle hand are embedded into the psyche of human beings. Our commune and connection with gardens informs literature, religion, community, and civilization as a whole.

Many garden scholars argue that the beginnings of what we now know to be gardens were in fact not made but discovered. These areas could be a small clearing in a forest, a patch of wildflowers by a stream, a string of trees that swept the topography just so. Maybe you’ve even stumbled upon an area like this out in nature yourself. In his book The History of Gardens, Christopher Thacker emphasizes that “the very draw of the locus amoenus (garden of delight) is that they were untended spaces and that their nature would be tarnished with man’s intervention.” In literature these spaces were sacred, often being occupied only by the gods or other mythical beings of importance as underscored in Homer’s Odyssey.

“A great fire blazed on the hearth…

Thick, luxuriant woods grew round the cave, alders and black poplars, pungent cypress too, and there birds roosted, folding their long wings… And round the mouth of the cavern trailed a vine laden with clusters, bursting with ripe grapes. Four springs in a row, bubbling clear and cold… Soft meadows spreading round were starred with violets, lush with beds of parsley. Why, even a deathless god who came upon that place would gaze in wonder, heart entranced with pleasure.”

Delight is just one source for the origin of gardens, others are sources in the production of food, or science, or often a blend of all three. Read on to learn more about how this manifested in the early construction of some of the oldest recorded gardens across the world.

Thebes and Amun-Re

The ancient gardens of Egypt are unfortunately no longer around, but their legacy remains in the depictions on the walls of gravesites and tombs. In their first iteration, these gardens were often originally constructed by pharaohs and sometimes gifted to other nobility. Royalty did not maintain these gardens though– that work was left to a large network of skilled individuals. Second iterations of these gardens evolved into funerary and memorial gardens. In both forms, they were used for leisure, entertainment in the form of music or dance, and for lavish banquets, religious observances or other rituals.

The Eighteenth Dynasty (1550- 1292 BCE) is classified as a height of ancient Egypt’s power. As a result, much of the remaining early garden depictions are seen in the series of over 400 tombs and chapels from this period. The precise elements of course varied, but as archeological remains show, most gardens consisted of three main elements: walls, a pond, pool, or canal, and plants.

Image of fresco from Thebes Tomb #96, via New York Public Library Digital Collections.

One commonly cited and well-preserved example of this combination is the garden of Amun-Re. As scholar Jayme Reichart defines it, the “Domain of Amun refers to all the lands, mundane and sacred, controlled by the Amun cult on the East and West Banks of Thebes.” This garden depicts a myriad of elements within the walls and distinct smaller sections defining those elements. Throughout these sections are avenues of large sycamore figs (Ficus sycomorus), a plant associated with death and resurrection. The presence of larger trees is significant, since the banks of the Nile River consistently flooded, trees weren’t always able to reach a mature size. Grape vines are also depicted growing on pergolas at the center of the garden where they were used to make wine and offer shade. The third element of many formal Egyptian gardens is also illustrated here, with the presence of several symmetrical pools on either side and a canal. Incorporating these three elements meant these gardens were not only a source of leisure but of production and recreation.

Ghent Botanical Garden

Situated in the Flemish Region of Belgium, the Ghent Botanical Garden boasts over 10,000 species of plants. This mass accumulation of plants is a result of over 200 years of acquisitions.

During his conquests in Europe, Napoleon set his sights on making the Netherlands a part of his “Grand Empire”. As a result, Ghent became the headquarters of the Scheldt and Lys Department (named after two rivers that run through France) of the French First Republic. Each headquarter was required to establish a school of science, equipped with a library, research collections, and a botanical garden.

Another director was Jean Henry Mussche (1765-1834). The genus Musschia, in the Campanula family, is named after him.

Officially the Ghent Botanical Garden opened in July of 1797. In it was a collection of herbs and some donations from André Thouin, who served as a director of the National History Museum in Paris, the botanical gardens of which were established some 100 years prior by Louis XIII. Of these contributions from Thouin were some of the earliest dahlias to be introduced to the country. Overseeing everything was Bernard Coppens, the garden’s first director. During his tenure he purchased collections from Ename Abbey, a monastery some suggest is home to the first reforestation projects in Europe.

In 1804, the garden changed hands from Napoleon's First Republic to the city of Ghent and in 1818 it joined the University of Ghent. In the later portion of the 19th century they were ‘outgrowing’ their space and began scouting a new location. This location was on the edge of the newly established Citadel Park and has remained there ever since. As its founders intended, it is still a place of plant research and study, with collections from Africa, Central America and China.

Hortus botanicus Leiden

Engraving of the Hortus Leiden done by Pieter Pauw, anatomist and botanist Pieter Pauw, published in 1601.

Moving slightly north, the Hortus botanicus Leiden is one of the earliest and oldest botanic gardens in Europe. Similar to the Ghent Botanical Garden and other gardens established at that time, Hortus was intended to be a center for teaching and for the study of plants and their medicinal properties. Following its formation in 1590 the newly formed University of Leiden greeted the arrival of botanist Carolus Clusius just three years later. He had arrived in the Netherlands upon request from the University to serve as scientific director and, due to his extensive expertise and reputation in international circles, quickly began building up the collections. One of the plants he brought with him and planted at Hortus were tulips, which established foundations for the Netherlands to become the tulip trading capital of the world. Another seminal contribution he published during his tenure was Rariorum plantarum historia. This contained generous descriptions of the plants and specimens he observed and with it the coupling of detailed illustrations which is regarded as a prime example of the industry standards of that time.

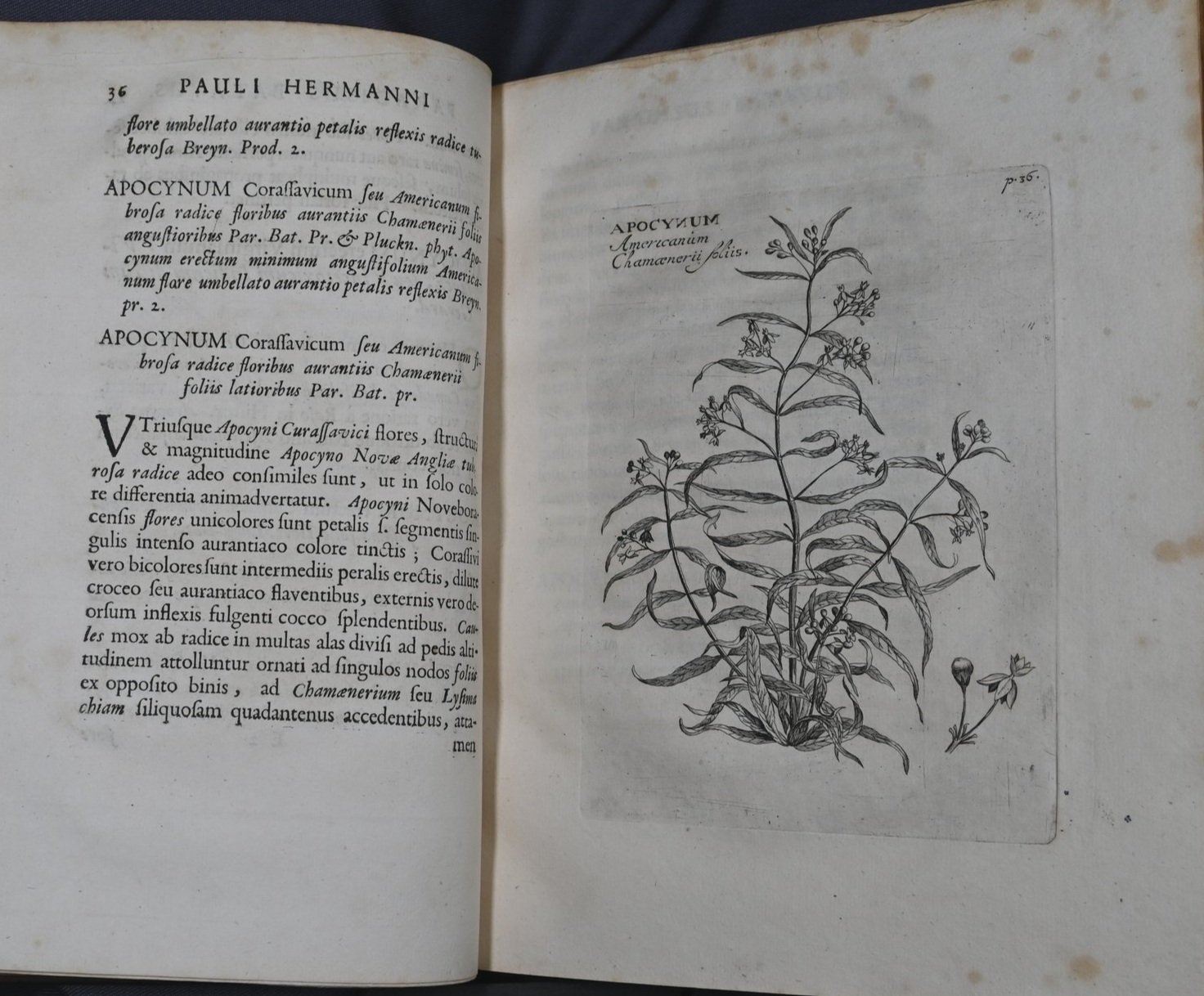

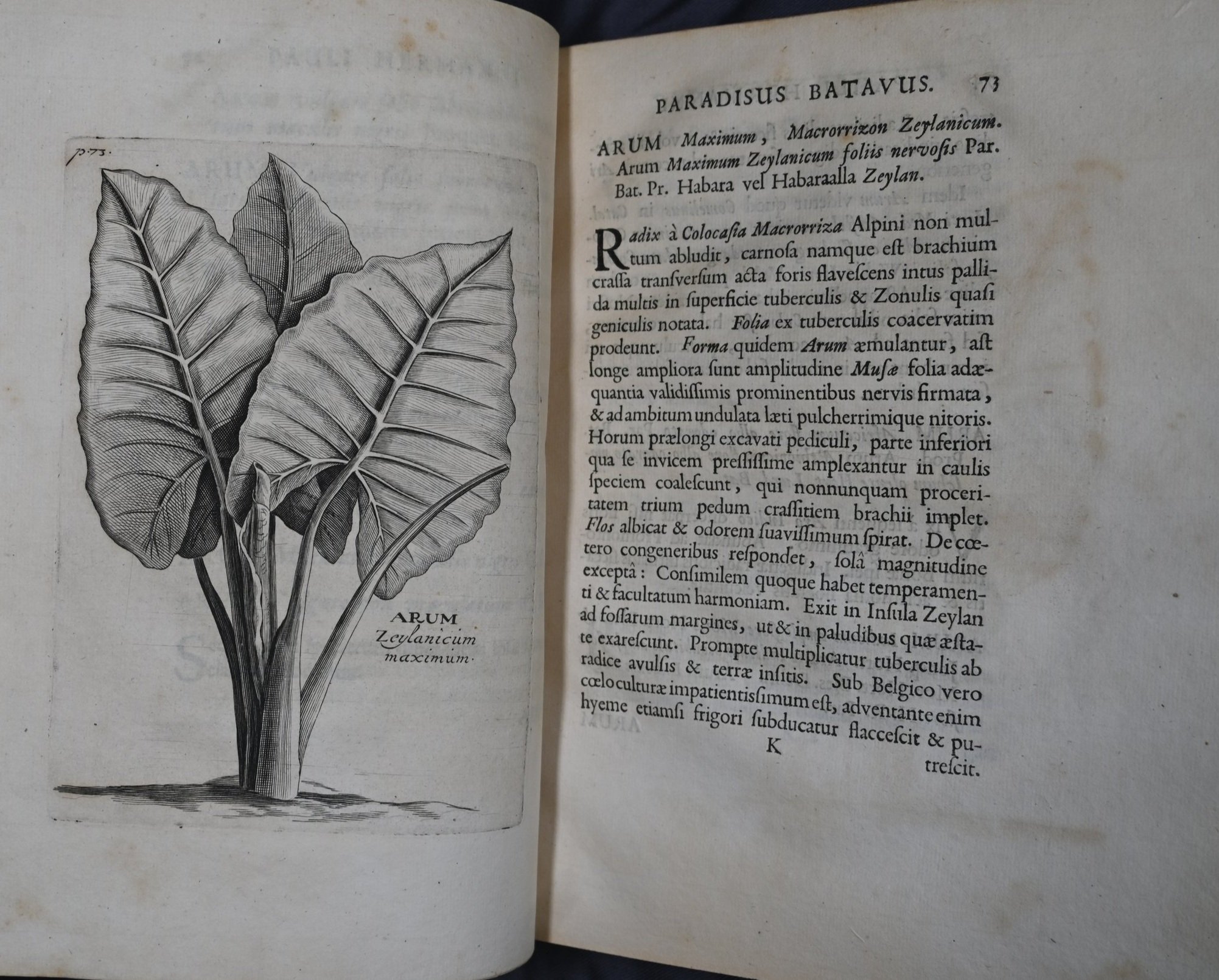

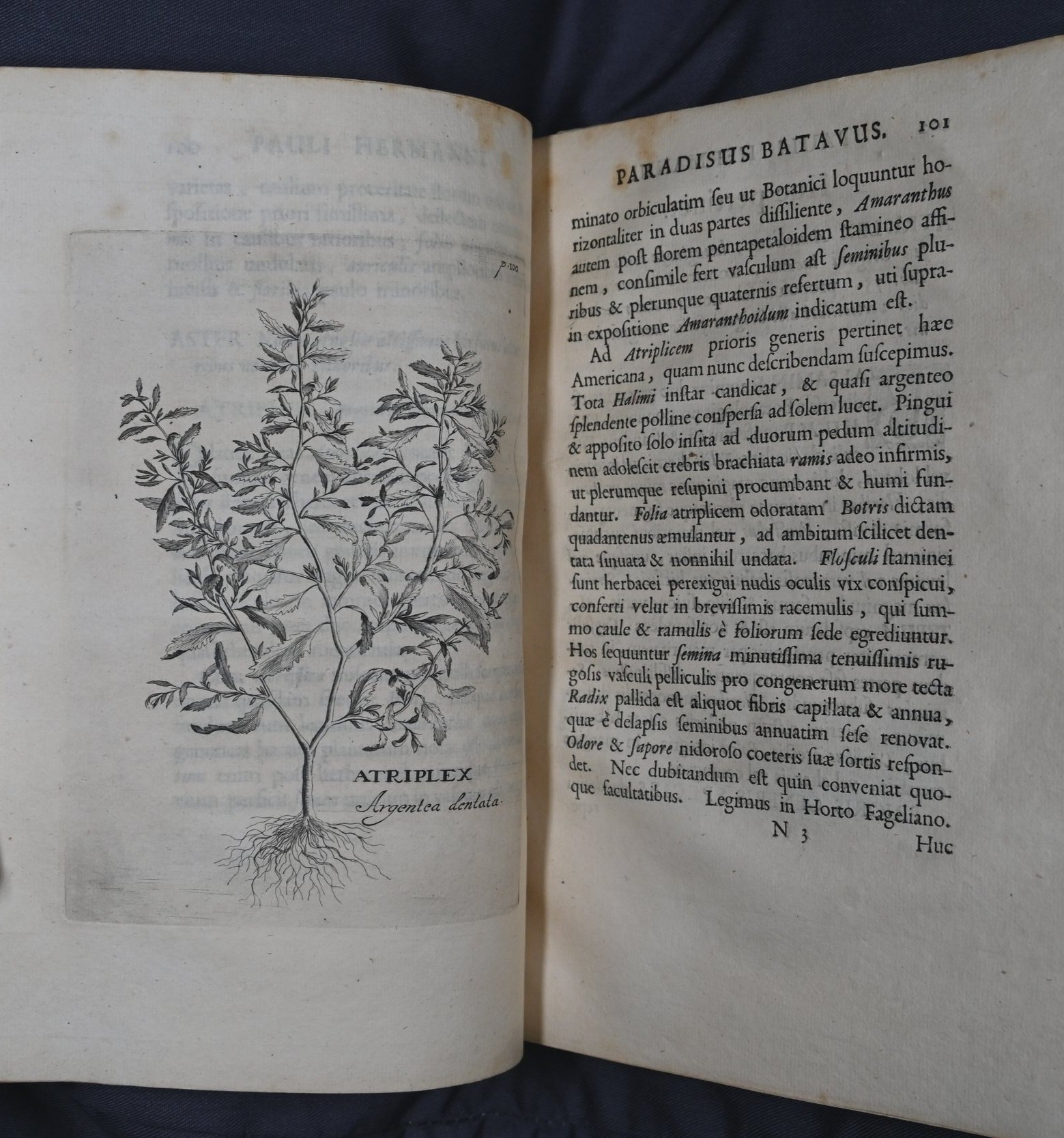

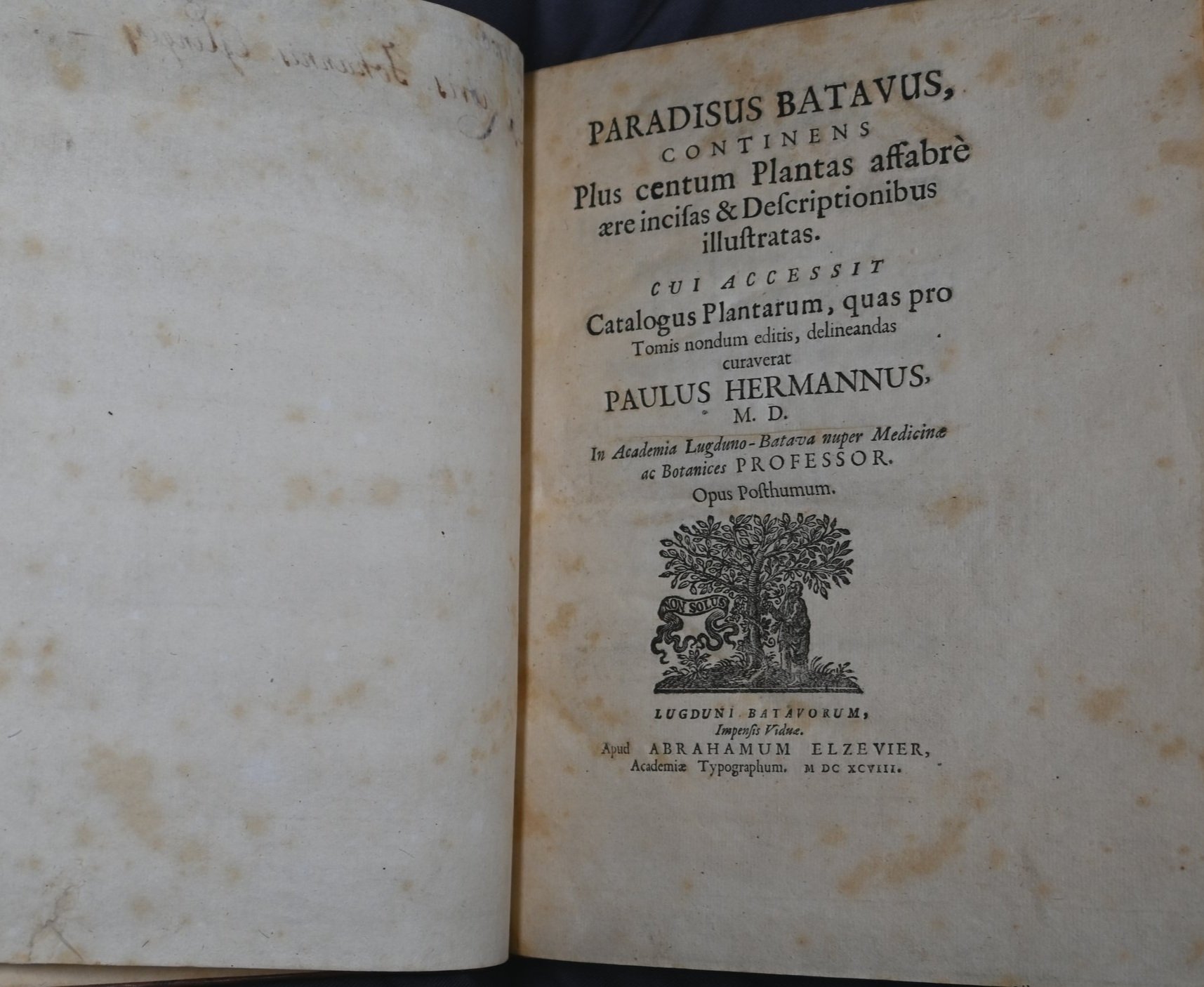

Throughout the 16th and 17th centuries the garden and its directors ventured to other parts of the world, partnering with the Dutch East India Company to collect plant specimens. From its initial thousand or so species in 1594, the collections grew to three thousand by 1685, at which point Paul Hermann was serving as a director. Today the garden houses close to 4,000 specimens from all over the world. Some of the early collections still remain in the Hortus, like a tulip tree (Liriodendron tulipifera), planted between 1710 and 1720 and a Ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba) planted around 1740.

Thank you to Head Librarian Tony Willis for his insights and assistance with this blogpost.

References:

28-10-2022, 19-10-2022, & 22-06-2022. (n.d.). History. Hortus Botanicus Leiden (English). Retrieved April, 2023, from https://hortusleiden.nl/en/the-hortus/history

Ghent University. (n.d.). History of Ghent's Botanical Garden. History of Ghent. Retrieved April, 2023, from https://www.gum.gent/en/history-of-ghents-botanical-garden

Reichart, Jayme Rudolf. Pure and Fresh: A Typology of Formal Garden Scenes from Private Eighteenth Dynasty Theban Tombs Prior to the Amarna Period. 2021. American University in Cairo, Master's Thesis. AUC Knowledge Fountain.

Swan, Claudia. “The Uses of Botanical Treatises in the Netherlands, c. 1600.” Studies in the History of Art, vol. 69, 2008, pp. 62–81. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/42622432. Accessed Apr. 2023.

van Uffelen, Gerda. “Hortus Botanicus Leiden.” SiteLINES: A Journal of Place, vol. 2, no. 1, 2006, pp. 6–7. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24889256. Accessed Apr. 2023.