Marvelous Mushrooms

OSGF

As we transition away from summer, mushrooms are beginning to appear in the landscape. While spring is often thought of as the prime time to forage for edible mushrooms like the highly sought morels, the months of September and October are also ripe with fungi. This is due to the cooling temperatures and higher rainfall we receive in the Eastern Hemisphere which in turn creates an ideal climate for existing fungi to fruit.

What’s now a worldwide phenomenon, interest in mushrooms had a slow start. There are early recordings of mushrooms dating to prehistoric times and links to the Indigenous peoples of Mexico. Leading European taxonomists like Carl Linneaus devoted hardly any attention to the fungi kingdom, so as the fields of sciences were being developed, mycology was left behind. Thankfully, things began to take a turn during late 18th century Europe. The very first woman to describe a new fungal taxa did so during the height of Linneaus’s new taxonomic ordering. Read on to learn about a few of the female scientists and illustrators whose early work informed our understanding of mushrooms today plus see a few examples of phenomenal fungi from the collections of the Oak Spring Garden Library.

Anna Hussey (June 5, 1805)

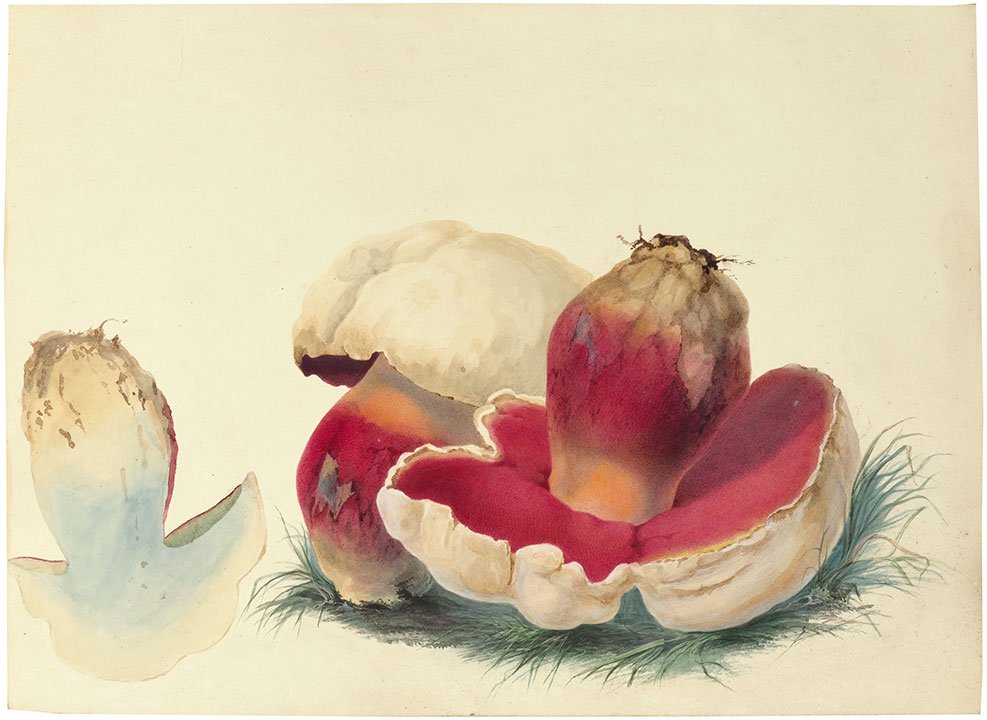

One of the earliest examples that exists of an illustrated mushroom dates back to 1461 in the Ortus Sanitatis, a highly referenced German encyclopedia of that time period. These early attempts at mushroom depictions were often lacking in any scientific accuracy and thus didn’t do much to contribute to the overall foundations of mycology. Fortunately, during the 17th and 18th centuries, the technologies of printing and overall practices of scientific illustration were advancing. These shifts made room for improvement as well as the incorporation of hand coloring which helped to further advance visual accuracy. One illustrator to emerge from this era whose works solely featured mushrooms was Anna Hussey.

Born in South East England in June of 1805, Anna’s interests in natural sciences and art were first introduced to her by her older sisters. Into adulthood she began her foray into the world of mushrooms from an artist's perspective despite the trends of other Victorian women of the time who focused on more ‘feminine’ plants and flowers. At the height of her artistic production she maintained correspondence with Reverend Miles J. Berkeley who holds the title as the “father of British mycology.” Berkeley, who described over 6,000 species of mushrooms during his lifetime, assisted with identifying the mushrooms she was illustrating while Anna would provide him with her collected specimens. Berkeley later went on to name a genus of mushrooms, Husseia (later renamed Husseyella to avoid confusion) in her honor and referred to her as, “a friend [...] whose talents well deserve such a distinction.”

Her most notable work is Illustrations of British Mycology which contains over 160 drawings. These illustrations were intricately detailed and often included depictions of their habitat and were accompanied by descriptions of each species with personal anecdotes and comments. The majority of her focus was on morels and puffballs which are held under the genus Hymenomycetes.

Flora W. Patterson (September 15, 1847)

In mid to late May, tourists descend to Washington DC by the bus load to get a glimpse of the pink and white cherry blossoms that line the perimeter of the Tidal Basin. This iconic feature of our nation’s capitol was a gift from Yukio Ozaki, the serving mayor of Tokyo in 1909. However the trees that tourists and residents alike enjoy today are not the original 2,000 trees that were initially shipped over– those were burned at the recommendation of the serving Mycologist at the USDA, Flora W. Patterson and her colleagues Nathan Cobb and J.G. Sanders.

It’s believed Flora’s interest in biology was sparked after she began taking biology courses in 1895 at the University of Iowa, where her older brother taught. Wanting to continue to be near him, she made arrangements to attend Yale while he attended Harvard Law School.

Thinking all conditions for pursuing work at Yale had been arranged, she went there only to find the doors closed against her, women not being eligible at that time. – Vera K. Charles, Mycologia, Vol. 21

The rejection from Yale left her undeterred as she continued to pursue courses in botany and plant physiology at Radcliffe College for the next three years while also working at the Gray Herbarium of Harvard. It was during this time that she was trained in maintaining the herbarium’s fungal collections and expanded her knowledge of plant pathology and mycology.

Flora was a champion for the field of mycology and unsurprisingly a lover of all things mushrooms. In her 1915 bulletin Mushrooms and other common fungi she even shares a recipe for mushroom “katsup”. Image via Scientific American.

Fast forward to 1895, Flora had begun working for the U.S. Department of Agriculture as the Assistant Pathologist and also worked in the department’s herbarium. This is a role she would serve in for nearly three decades during which she also served as the keeper of the U.S. National Fungus Collections, contributing nearly 96,000 specimens. It’s now one of the largest reference collections in the world, all thanks in large part to Flora’s foundational efforts.

Elsie Wakefield (July 3, 1886)

From literary icons to botanists, Kew Gardens has been a significant historical waypoint for a number of disciplines throughout its history. For the history of mycology in Europe, Kew also served as a hub of activity. One of the primary founders of Kew’s mycological work was George Massey, who became the first Head of Mycology in 1892. The woman who assumed that position following his death was Elsie Wakefield.

Elsie began at Kew in 1910 as George’s assistant. Prior to this position she traveled abroad to Munich after being awarded a Gilchrist scholarship to study at the Forestry and Botanical Institute. There she studied Hymenochaetales (which contain many wood-inhabiting fungi) with Professor Carl von Tubeuf, a mycologist and plant pathologist.

Image via Kew Gardens.

We understand from records at Kew that early in her position, Elsie began focusing on the Basidiomycetes fungi group which include mushrooms, puffballs, jelly fungi, boletes, chanterelles. Through several papers published in later years it became clear that she took a keen interest in the study of Caribbean fungi. In fact, in 1920 Elsie traveled to the Caribbean through a scholarship offered by her former alma mater, a feat that was less common for women of that time period.

She later moved on to assume the role of Head of Mycology at Kew for nearly 40 years before being appointed Deputy Keeper of the Herbarium for 6 years. Her formal education and expertise on the subject should have garnered more regard and higher compensation but she held these positions at a pay that was substantially lower than that of her male colleagues. Of her many contributions, she published nearly 100 papers and two comprehensive field guides of British mushrooms, which contain botanical illustrations all done by Elsie.

Sarah Stone

Little is known about our last entry, Sarah Stone. What we do know remains from her illustrations which were produced in England between the years 1777 and 1820. The subject of her works spanned all areas of natural history, not just mushrooms. This was in part due to the patrons who sought out her artistic abilities. One patron of note was Sir Ashton Lever, a collector of natural objects and friend of Captain James Cook. Lever commissioned Sarah to illustrate his collections which were housed in the Holophusikon (referred to also as the Leverian collection or the Leverian Museum) and contained specimens and artifacts taken from Cook’s second and third travels. These illustrations were a testament to Sarah’s technical skills and in some instances are the first time a person of European descent made scientific observation of certain species.

The objects in the Leverian Museum were auctioned off in 1806. The watercolors Sarah produced provide insight into the expanse of the original collections.