Sisters in Botanical Illustration

OSGF

If the Brontë sisters are celebrity siblings of the writing world, then the Wharton sisters and Strickland sisters are perhaps the unsung stars from the “golden age” of botanical illustration. The height of this period in Europe spanned from the 18th century to the mid 19th century. During this time men and women were taken up with a passion for illustrating plants both native to Europe and ones taken from abroad.

To round out Women’s History Month, we are highlighting two sister duos whose works underscore the importance of women’s place in the formation of the field of botany and scientific illustration. Read on to learn about their contributions and to view the works in full as part of our ongoing digitization project of materials from the Oak Spring Garden Library collections.

Elizabeth Wharton and Margaret Wharton

(1793-1811)

Despite having created four botanical volumes on flowers, grasses and mosses, little is known about Elizabeth Wharton and Margaret Wharton. We do know that they were two of four sisters who were all living in Durham, a town in North East England. It’s likely that they were brought up with all the training provided to an aristocratic household, such as drawing lessons. Another major source of information about one of the sisters, Elizabeth, comes from the Biographical Sketch. In it the author outlines Elizabeth’s character and talents saying, “most paid of her time & attention was Botany; in which she was a very considerable proficient.”

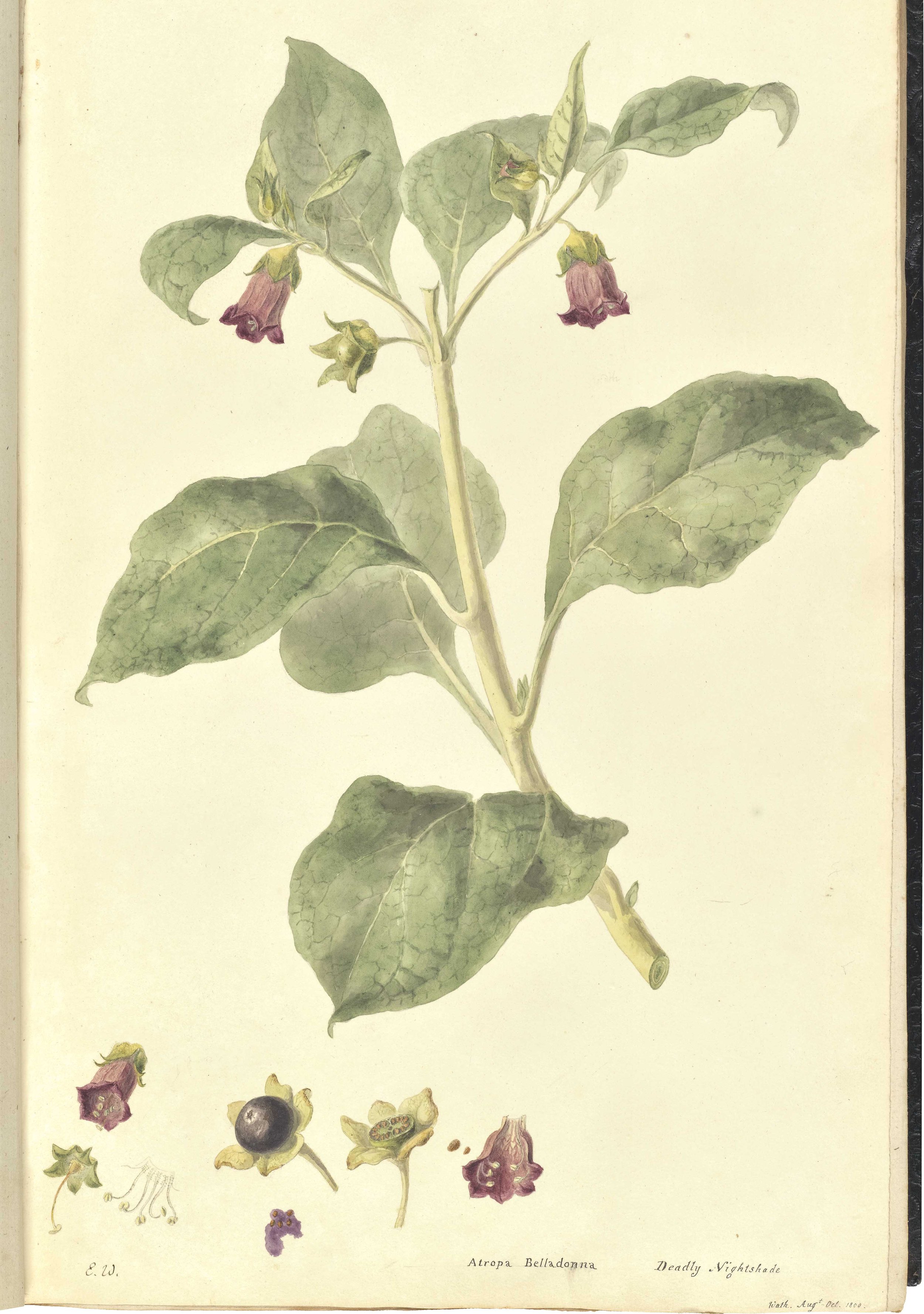

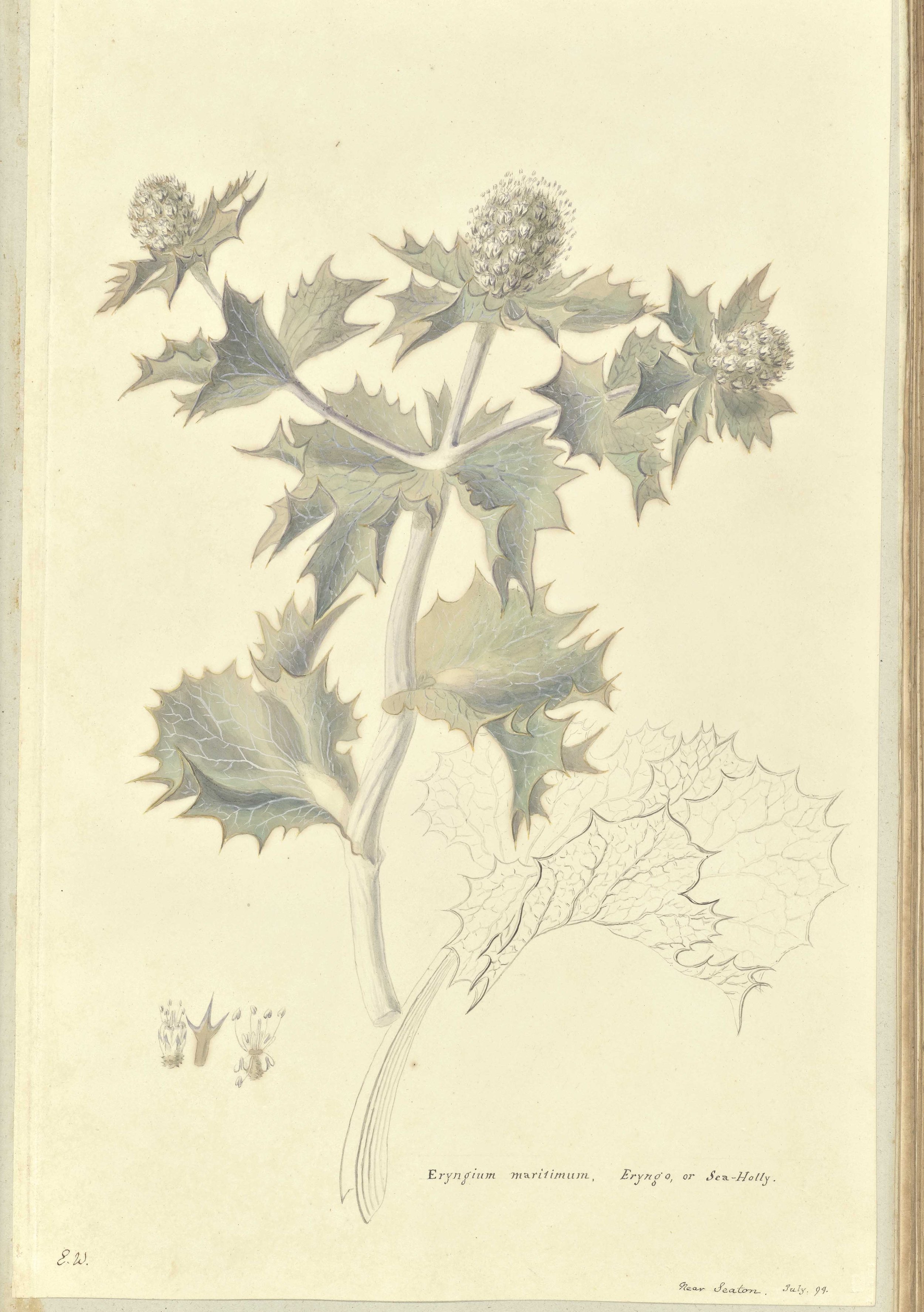

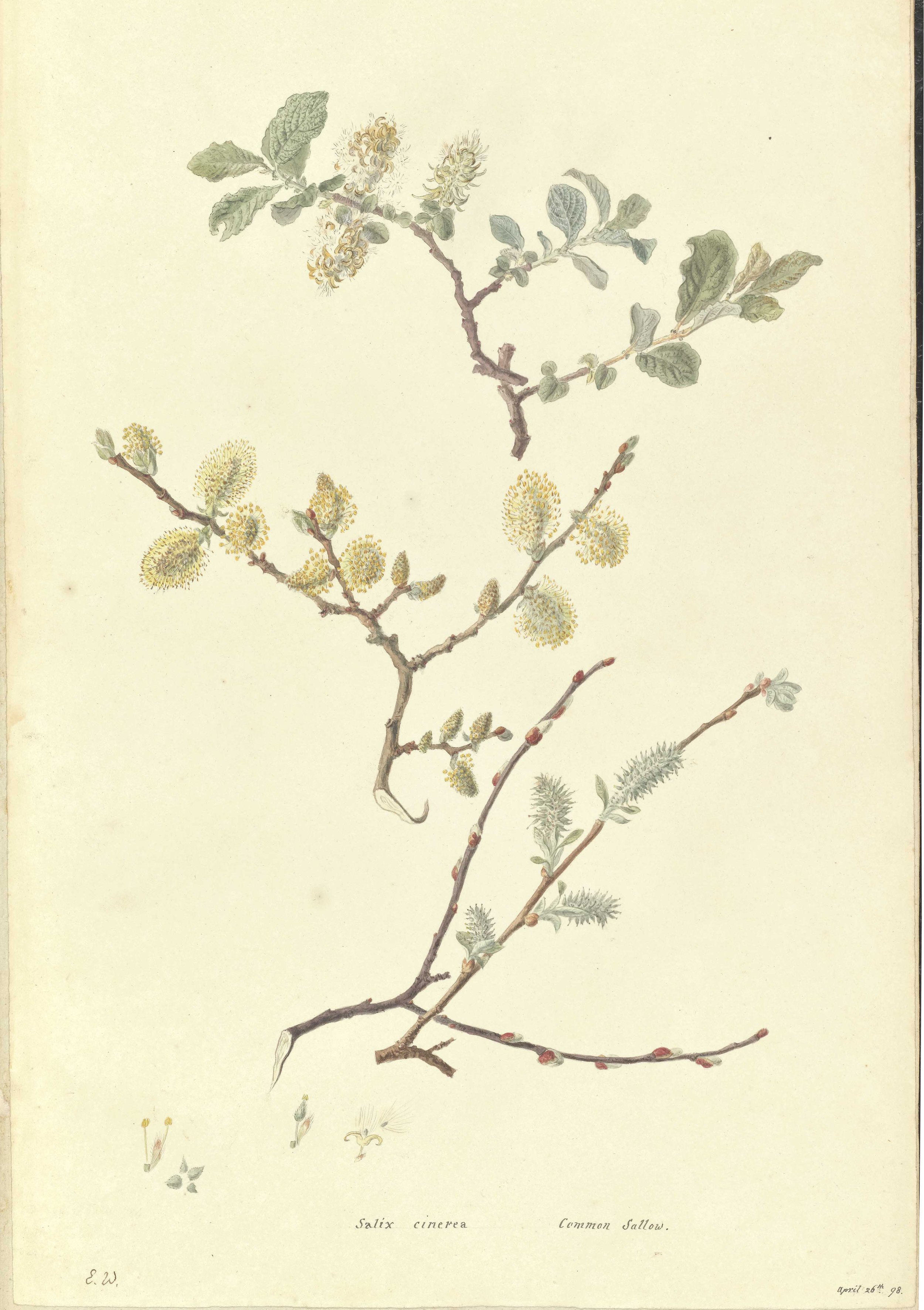

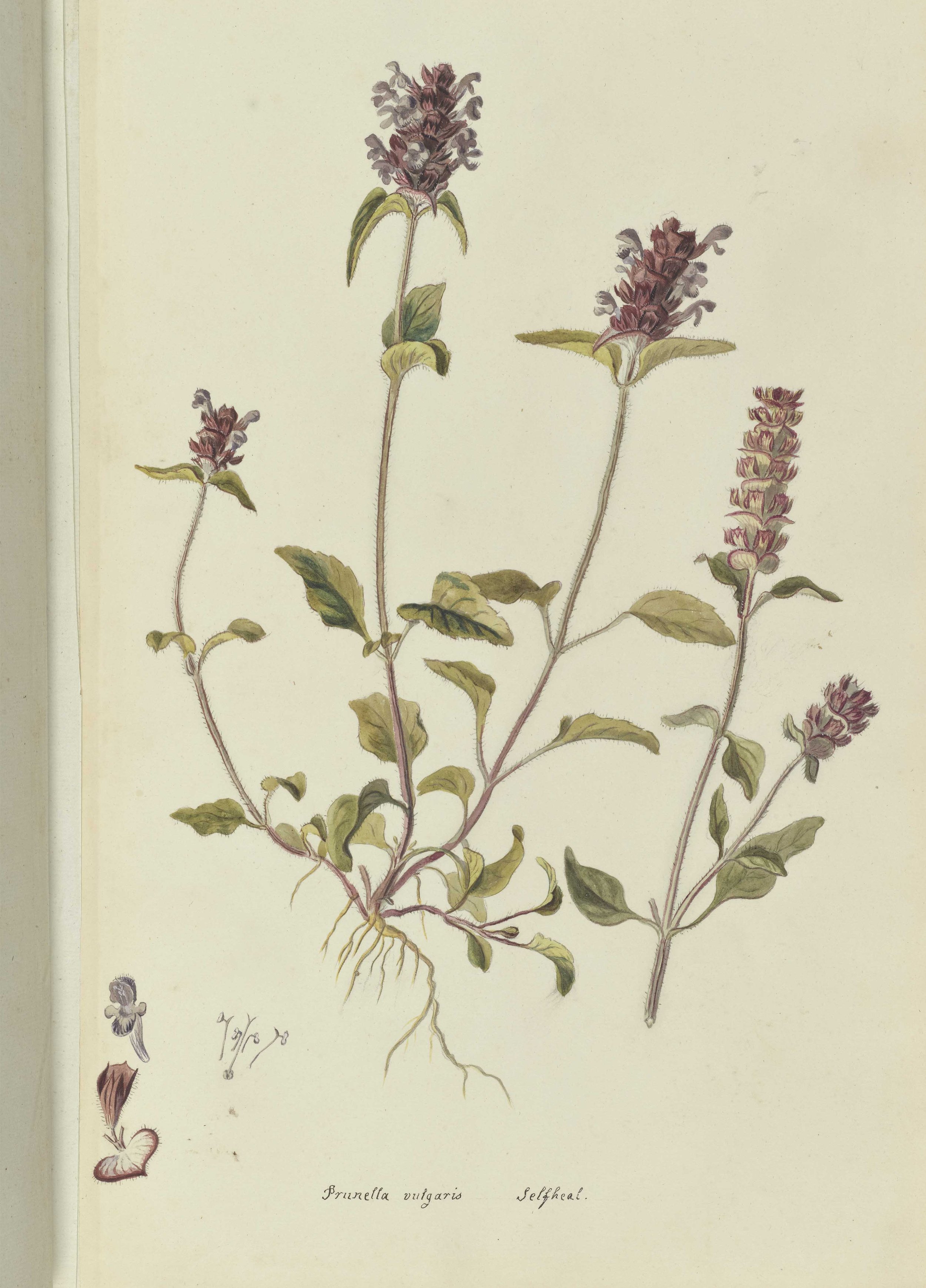

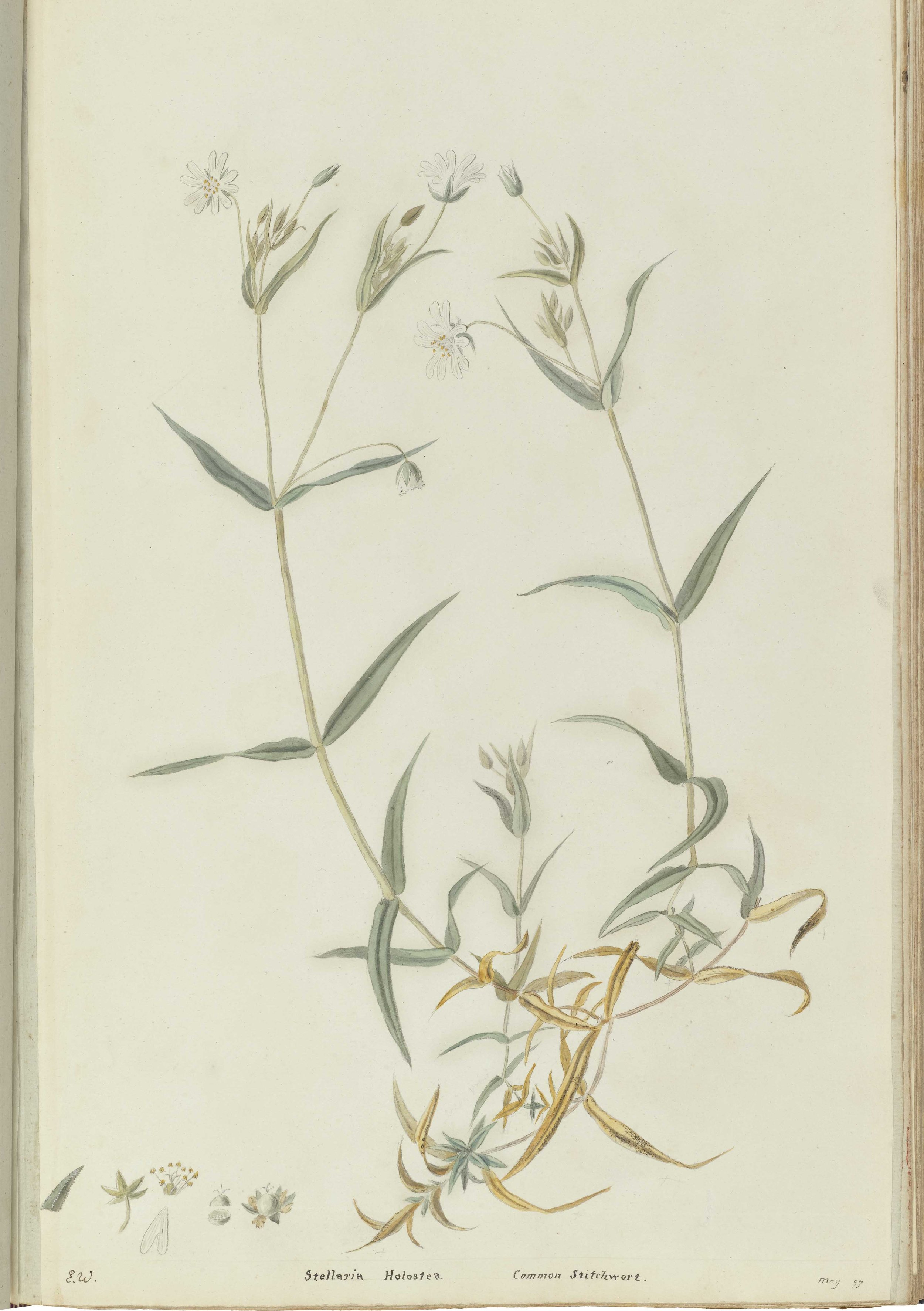

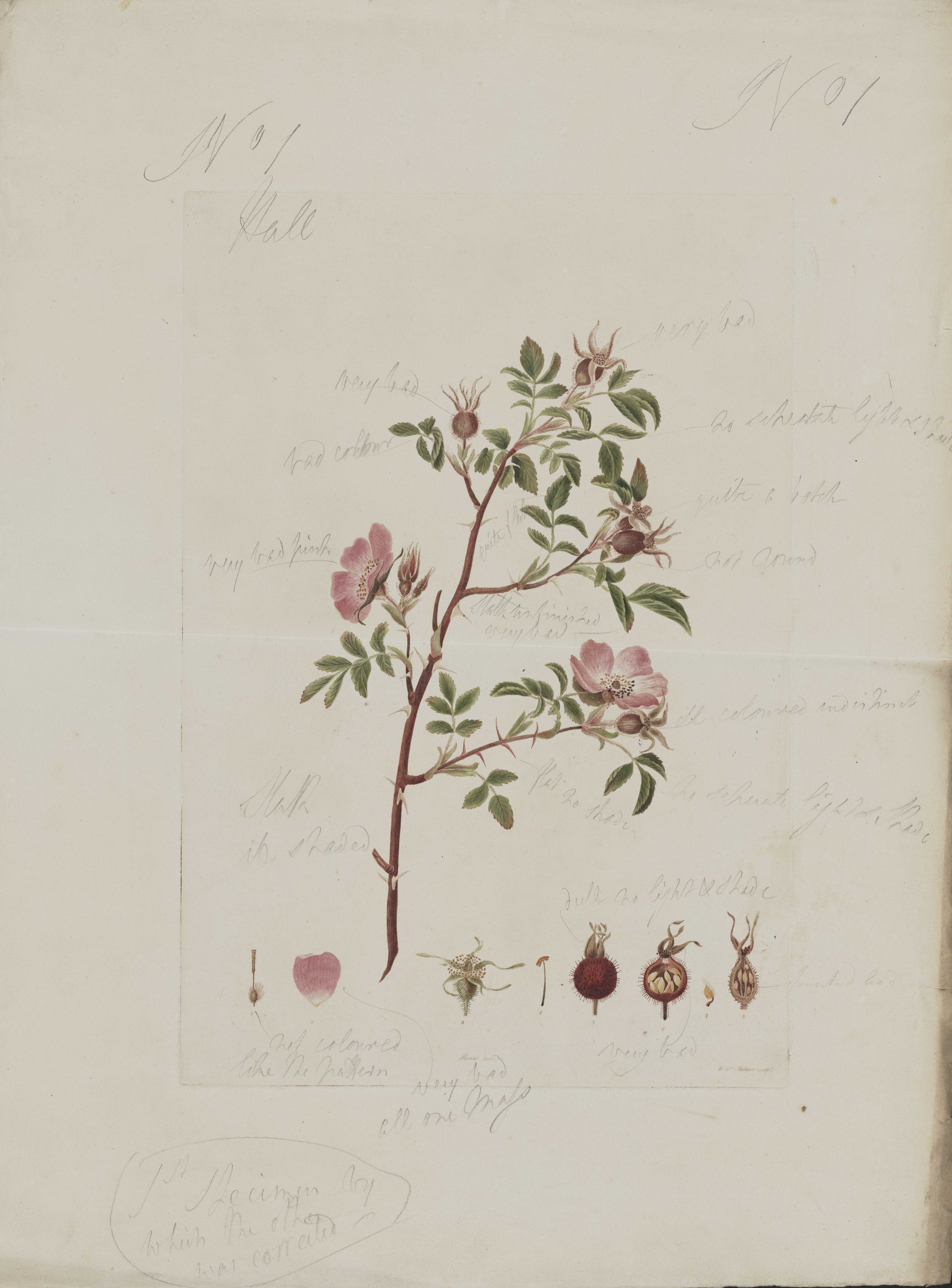

320 watercolor and pencil illustrations make up the first manuscript completed by Elizabeth and Margaret, British Flowers. The breadth of species covered in the two volumes includes plants like willow, violet, iris, orchids, water lilies, yew, juniper, and more. In the first volume, Elizabeth’s observational skills in particular are evident through her illustrations of Orchis mascula (now referred to as Orchis provincialis), the “Provence orchid”. On the next page, she illustrates the species, this time highlighting a potential new variety. In the floral diagrams she notes darker colored flowers as well as the presence of nectar guides and a wider labellum (or lip). These distinctions can be seen when looking at both of her illustrations side-by-side.

“Several folio volumes of British plants drawn in water colours with great spirit and fidelity, and with close regard to the individual character of the… subjects depicted attest her skill & industry-and would prove a valuable acquisition to science if published to the world. ”

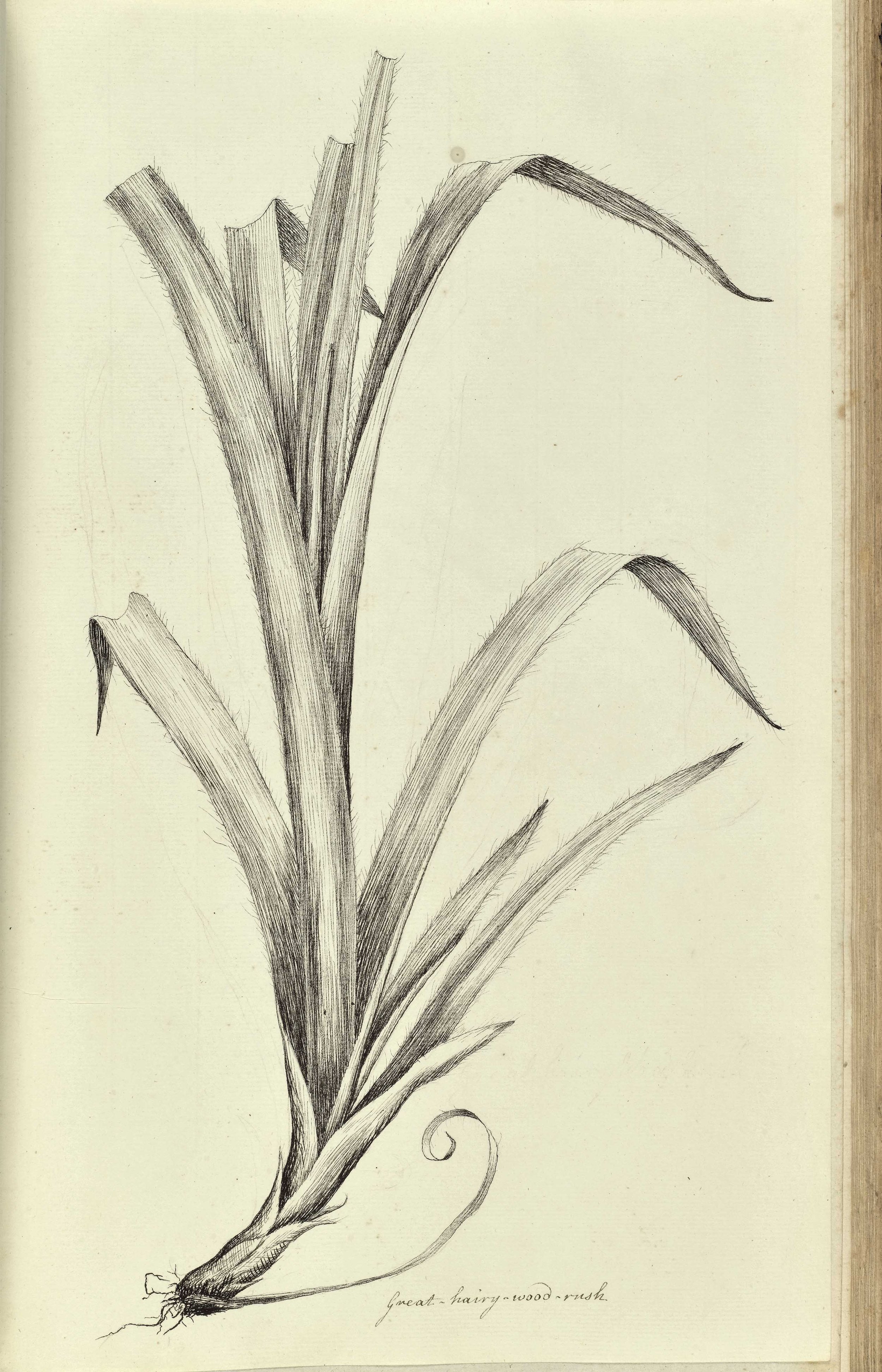

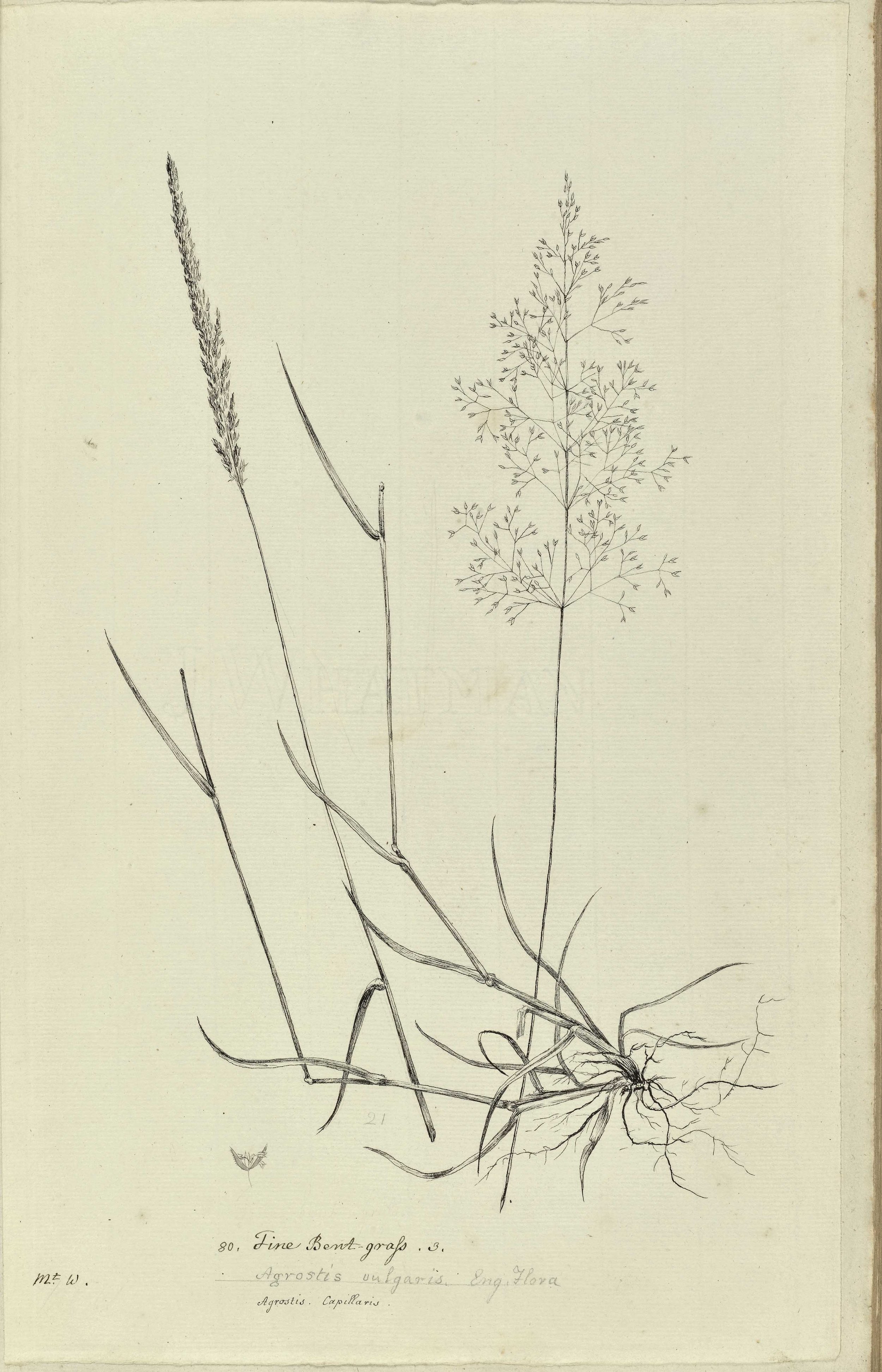

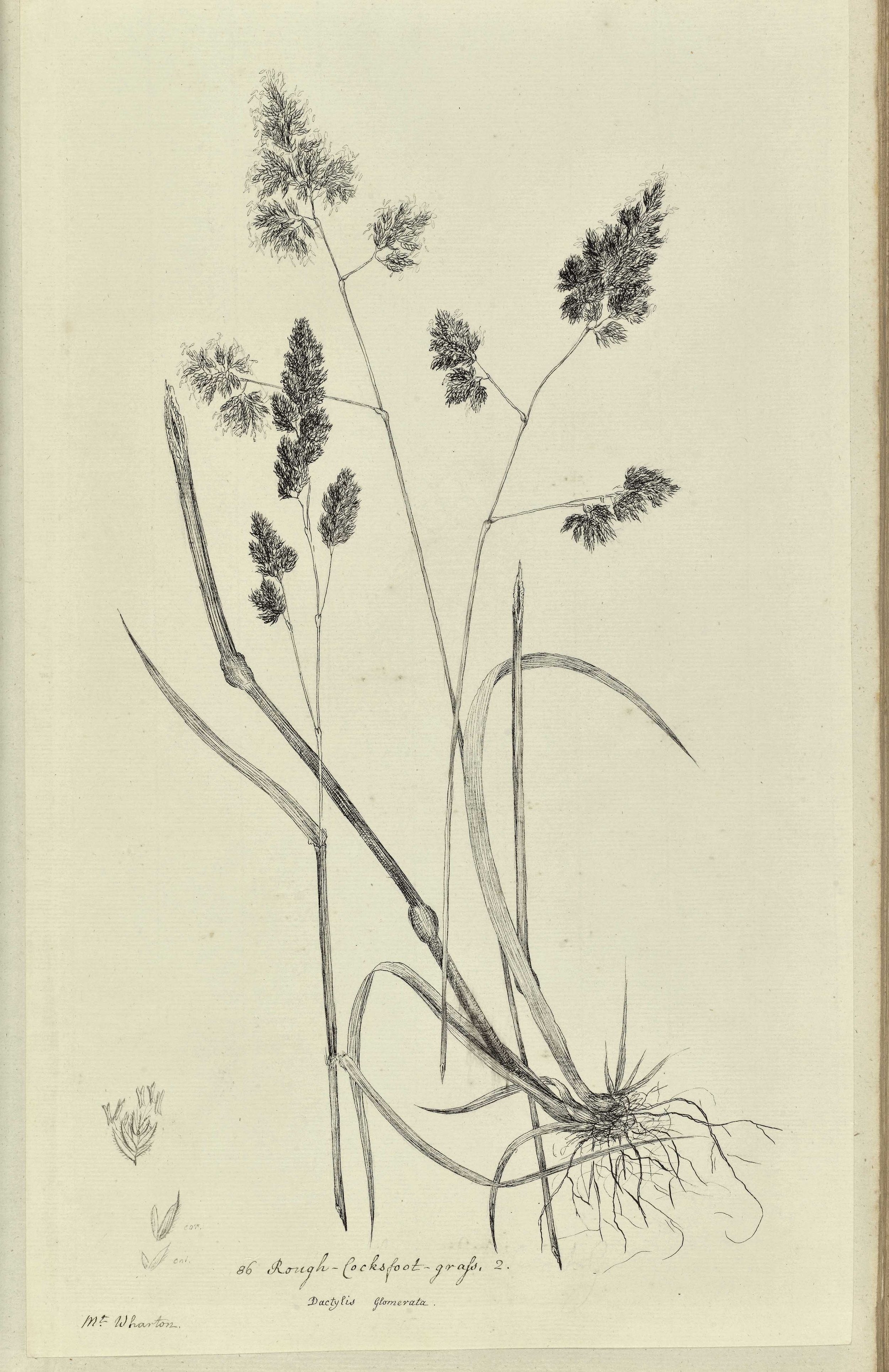

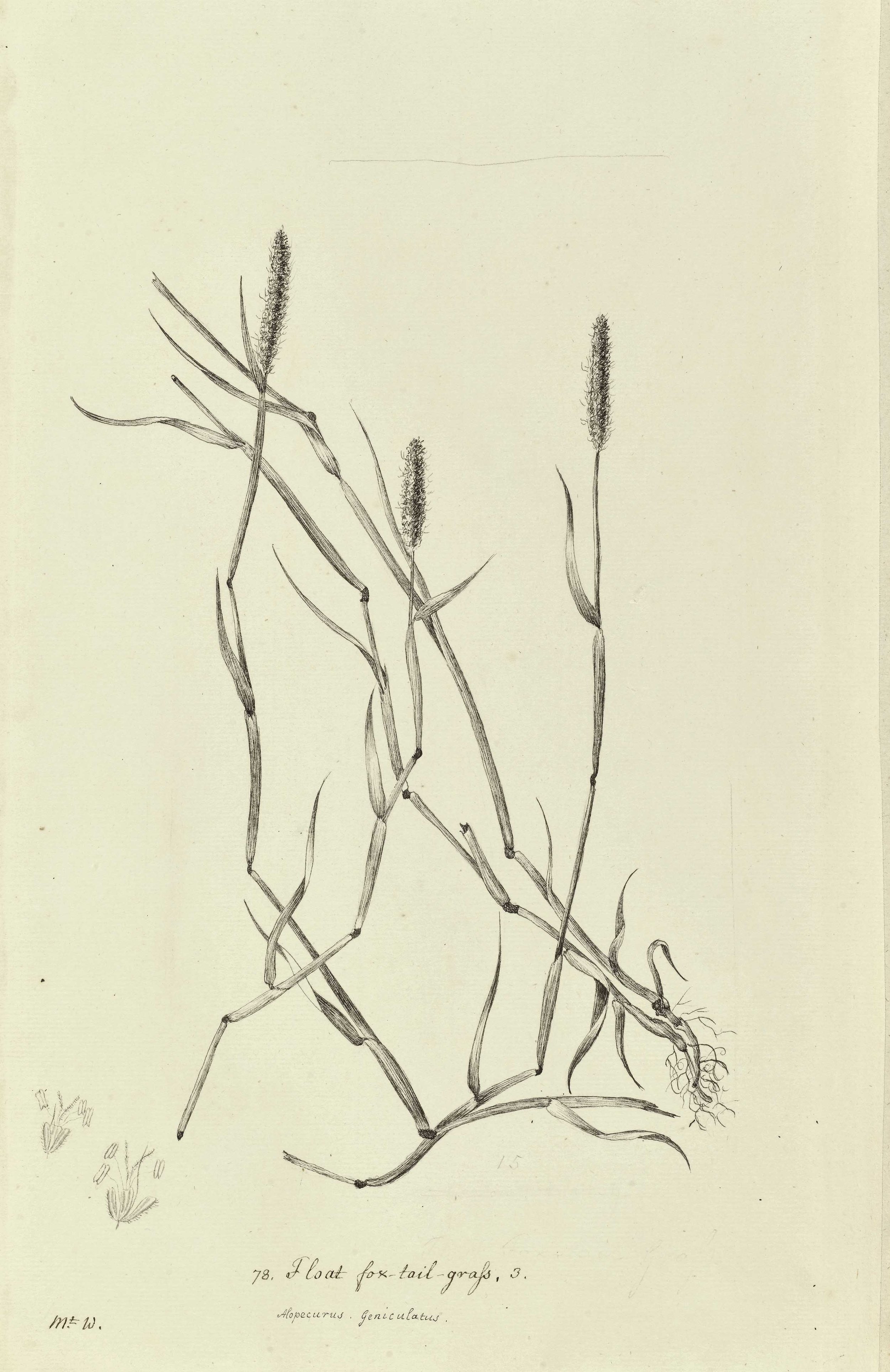

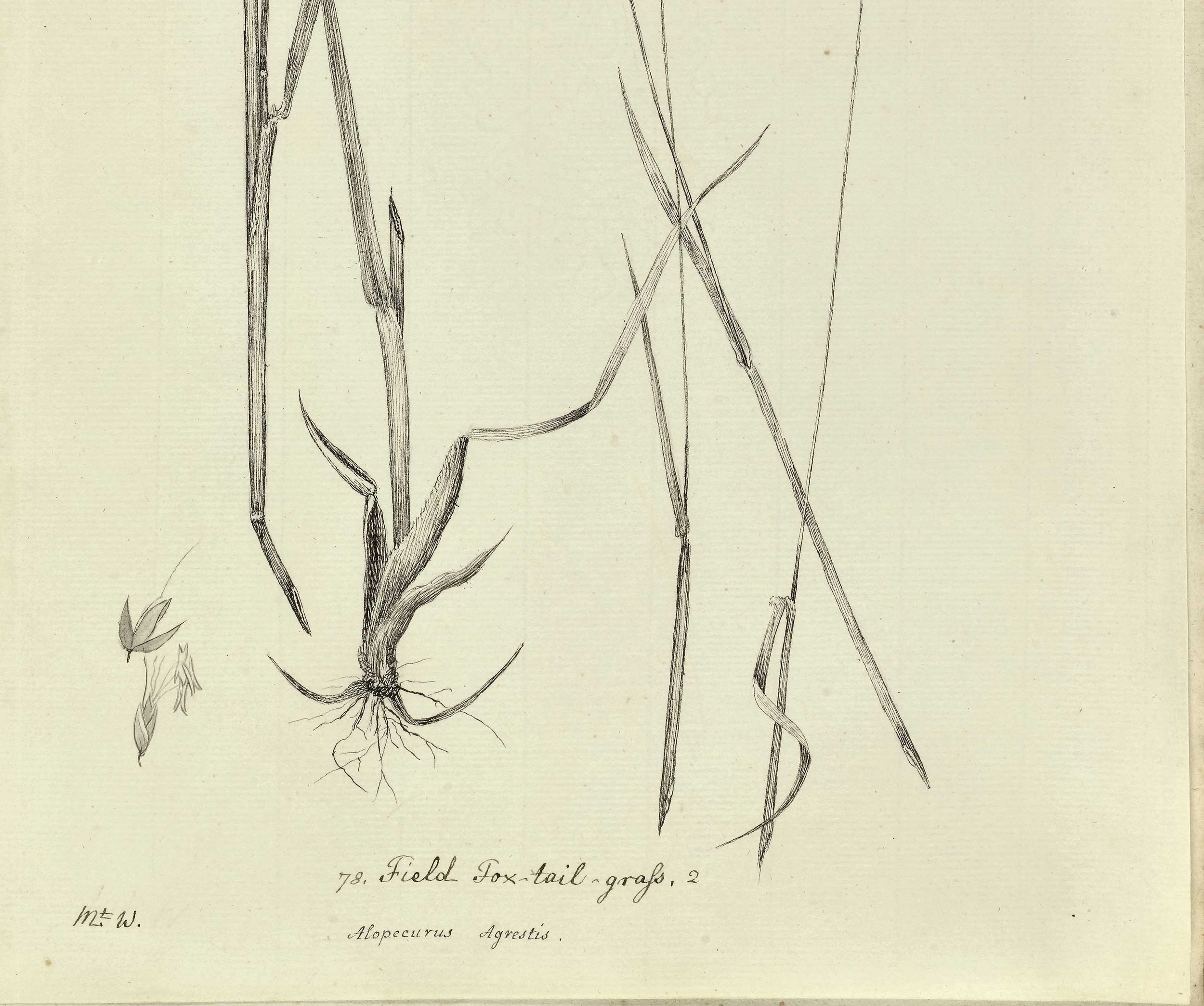

Undaunted by British Flowers, Elizabeth and her sister Margaret took on an even more challenging task of completing British Grasses—detailed fine leaves and complex reproductive parts and all. In British Grasses, the volume comprises 119 illustrations of members of the grass family, Poeacae. Along with the illustrations, there are a series of notes which contain a list of each species as well as description for each genus.

All three manuscripts the sisters completed were published between 1802 and 1827. This timeframe can be drawn in part by the recorded collection years noted in the right hand corner on certain pages of each manuscript. These collection dates and miscellaneous notes are the only reference points we have to the life of Elizabeth and her sister Margaret. The Biographical Sketch does allude to an early injury which later took hold as a paralyzing illness and is the only information we are left with in piecing together the rest of Elizabeth’s life, while Margaret and her other two sisters are omitted entirely. We are left, however, with their works, British Flowers, British Grasses, and British Seaweeds which all highlight the small but meaningful ways in which women were engaging with the field of natural history and botany.

Charlotte and Juliana Strickland

(1797-1809[?])

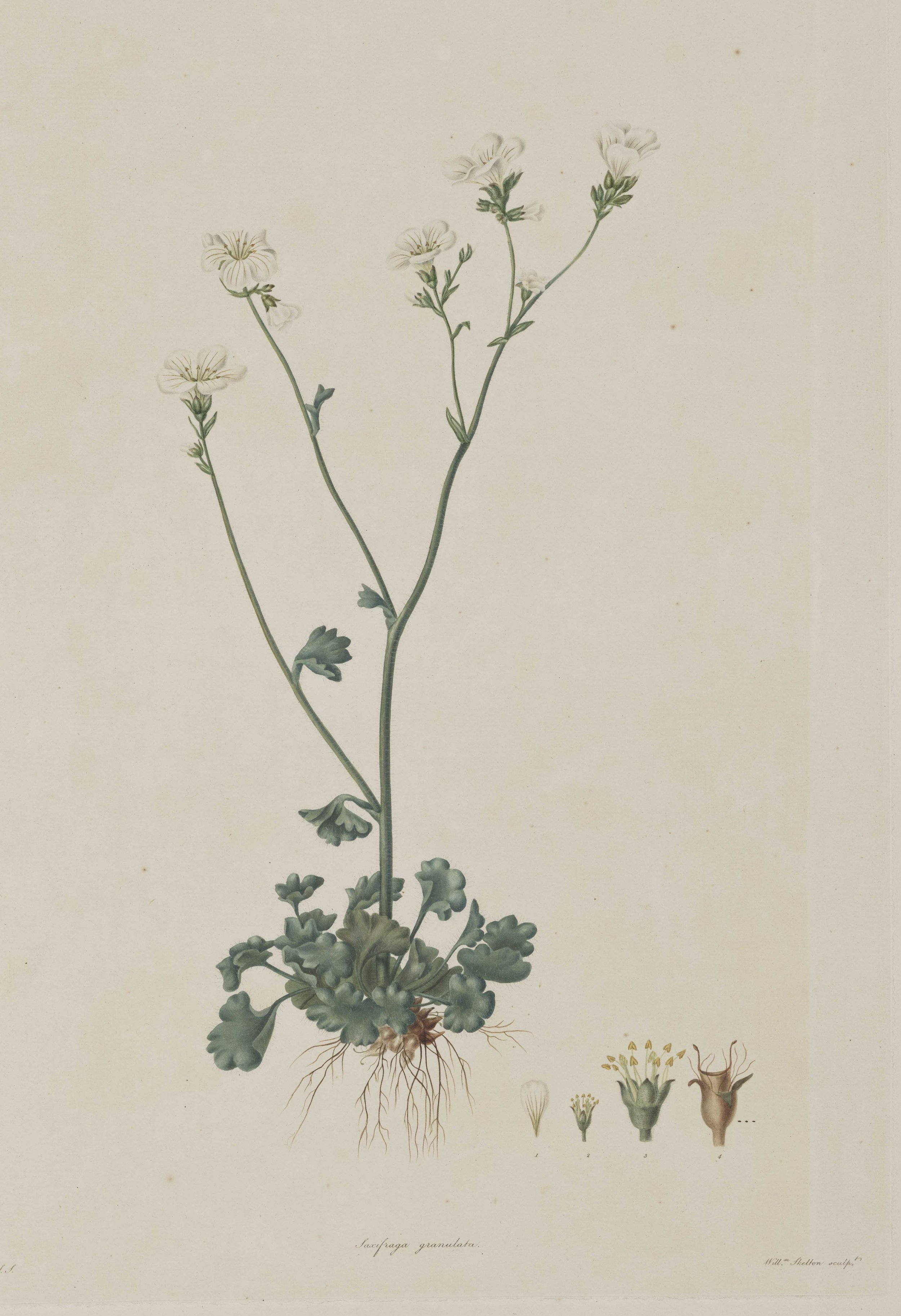

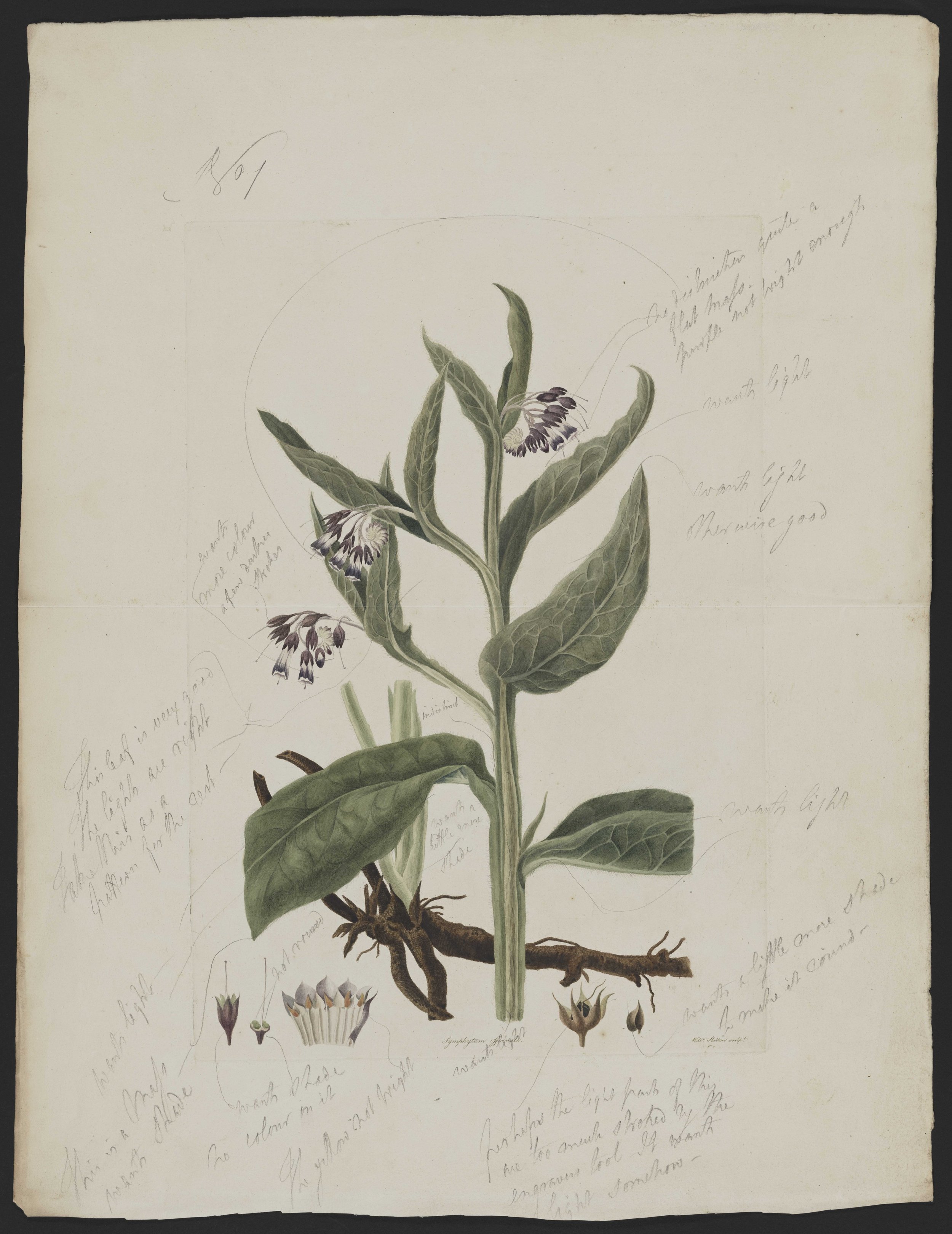

Our second set of sisters is, unfortunately, much like the first in that there’s not much information that speaks to their life or how they came to become botanical artists. The only glimpses we get are from their connection to the editors of their book, Selected Specimens of British Plants. Strickland Freeman (the sister's cousin and brother-in-law) is credited with editing the book. All three Strickland’s come from a pedigree that boasts other naturalists of note like the ornithologist Hugh George Strickland and William Strickland who is credited with introducing the turkey to England. It’s clear that they had an interest in botany and the natural world through these familial ties and through their dedication of the works to Sir Joseph Bank, renowned naturalist.

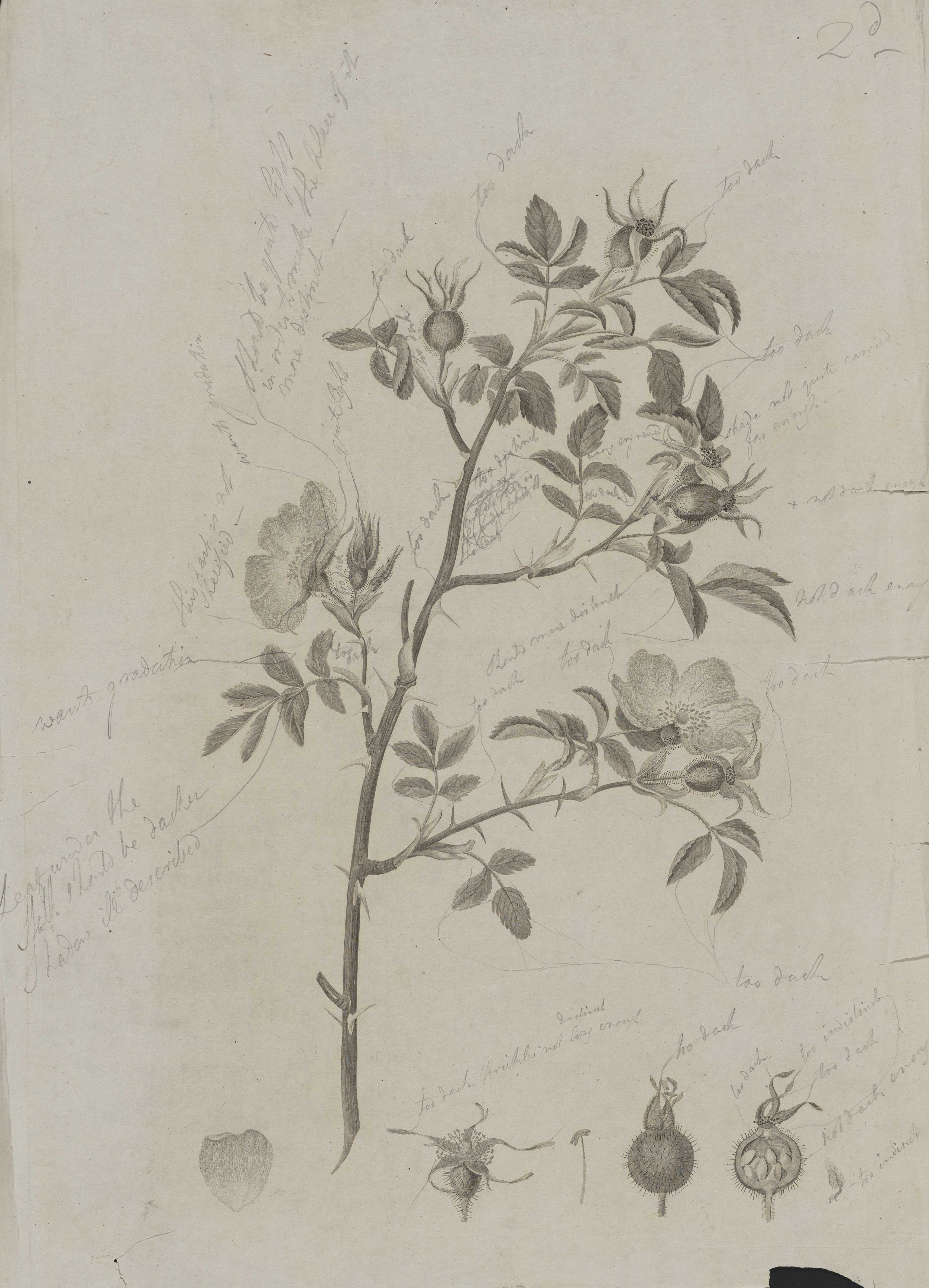

A majority of the plants are taken from their immediate landscape of Gloucestershire or from their home, Apperley Court. This note references a rose “found in the northern part of our island.”

Accompanying the final illustrations are a number of notes– likely made by Freeman Strickland. These handwritten comments critique the women’s coloring, shading and have other notes speaking to botanical accuracy of the illustrated plants. These back-and-forth drafts and comments present a rare insight into the process that likely many amateur's and professionals faced when publishing their botanical illustrations.

Dr. George Shaw, a naturalist and zoologist is credited with providing the botanical nomenclature of each specimen that the sisters illustrated. Beyond some archival records which indicate Juliana and Charlotte’s christening and dates of death, their history remains solely in their published work.