Mrs. Mellon's Orchids

Julie Olechnicki

In this blog series, Oak Spring’s interns and apprentices share their stories of working and learning in our gardens, fields, forests and farm. This post was written by our 2024 Horticultural Apprentice, Julie Olchenicki.

Few species of plants have captivated people for centuries quite like orchids. Taking the world by storm, orchids of every size and color are now readily available and can be kept alive by even the most novice gardeners. Thanks to our archives and garden records, we know that Mrs. Mellon also was swept up in the orchid craze. Read on as our Horticultural Apprentice, Julie, dives into the history of orchids and their history at Oak Spring.

When orchids were introduced to the gardening world, plant collectors and botanical institutions responded by sending droves of ‘plant hunters’ to search for them. Orchids at this time were considered a most exotic and delicate flower and the means to obtain them could be both expensive and dangerous. Mrs. Mellon was known to have a collection both at Oak Spring and at their home in Antigua throughout her lifetime. Records show invoices and inventory beginning in 1957 through 2006, presumably all ordered from reputable vendors or gifted from like-minded enthusiasts.

Bunny and Jean Schlumberger c. 1970. Photographer: Luc Bouchage.

History

One of the largest plant families, Orchidaceae contains over 28,000 recognized species with distributions on almost every continent on the globe. The first known reference to orchids was in a study titled Inquiry into Plants by Aristotle’s student, Theophrastus, around 300 BC. Since then, orchids have only gained exposure and popularity. During the 19th century, tropical plants indicated style and status during the Victorian era. As such countless publications were made on the topic, most notably by Charles Darwin who wrote Fertilization of Orchids in 1862. Breeding orchids wasn’t the only way people could grow their collections, as noted by Albert Millican who, in Travels and Adventures of an Orchid Hunter outlines his travels through Colombia to collect wild orchids. Regardless of the methods used to obtain them, in order to keep these new and exotic treasures, one had to have the right environment- like a greenhouse.

“In these greenhouses lush tropical landscapes could flourish, with palm trees of enormous girth and height and orchids of the most delicate form and colors.”

Mrs. Mellon’s Orchids

An inventory done in January of 1965 revealed there were 93 different species and varieties accounted for at Mrs. Mellon’s properties. Most were Cymbidium (49 varieties recorded), xOdontioda (35 varieties recorded), Oncidium (23 varieties recorded), and Phalaenopsis (11 varieties recorded). Dates of purchase are also listed on the inventory, the earliest being a pair of Cymbidium purchased in November 1957.

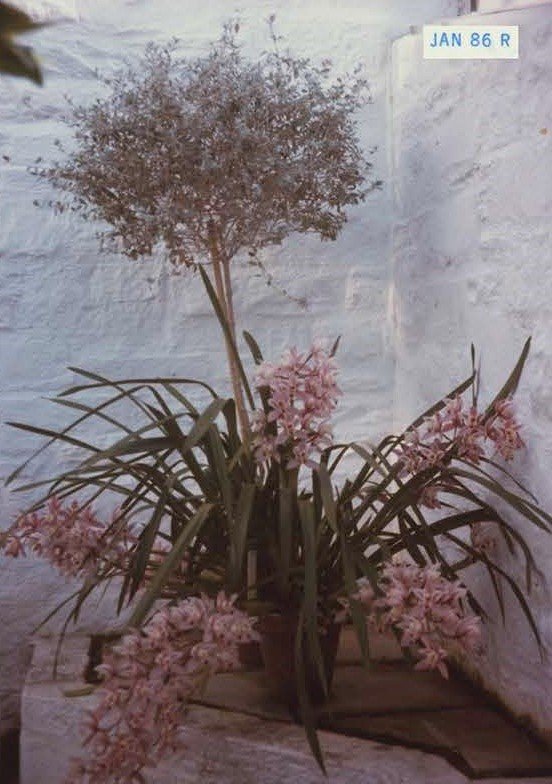

While there’s no location listed on the inventory, it can be assumed that it was done at Oak Spring. This is further solidified by the correspondence with Charles Pecora, the head gardener of the time and Lager & Hurrell Orchid Growers and Importers. In a letter dated from February 1965 Pecora writes, “Mrs. Mellon has a preference for colors such as blue, shades of orange and red, lemon yellow, white and greens. We are not interested in Cattleyas or their types.” He continues, “I might add that there is no special hurry about this as the house is not ready yet. However, with a list, plans can begin.” This letter insinuates that Mrs. Mellon was considering her potential orchid collection at Antigua and possibly storage for such collection before construction was complete. There were several shade structures and slat houses built at their home in Antigua, potentially to house orchids and other tropical types. The picture below depicts an open-air room off the dining room where several orchids, bulbs, and palms can be seen.

Photo from Oak Spring Garden Foundation archive collection.

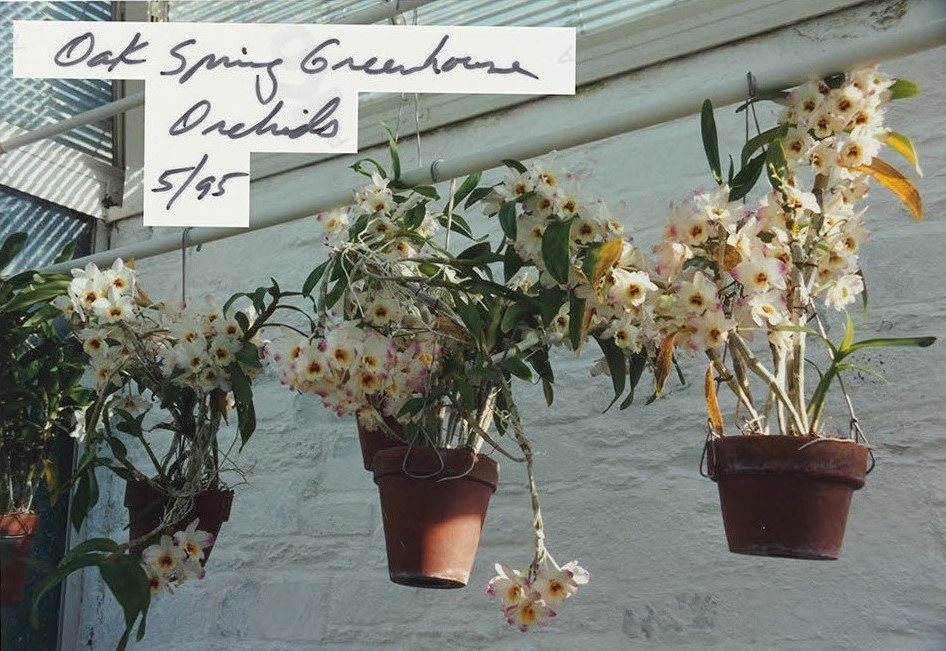

Currently in the formal greenhouse several genera of orchids can be found, including: Phalaenopsis, Paphiopedilum, Dendrobium, Medinilla multiflora, Vanilla planifolia, and Oncidium. The photos below, taken by George Shaffer, depicts a dendrobium orchid in the formal greenhouse dated for 1988, which still grows in the greenhouse today.

Pictures following depict other orchids in the formal greenhouse with dated ranging from 1988-2006, all taken by George Shaffer.

Phalaenopsis spp.

Moth Orchids

This is the most popular and readily available of all the orchids, with 80 accepted species and countless hybrids. Most are native to Southeast Asia and have suffered from over collection and habitat loss. Phalaenopsis are one of the first recorded tropical species among the Victorian collections and remain popular today due to their ease of propagation and flowering under artificial conditions. They tolerate temperatures anywhere in between 65-95 F, with moderate humidity and relatively low light. This means most everyone can grow them in their homes under no special treatment.

Due to hybridizing, almost every color bloom is possible with some even having spots or stripes. The blooms themselves can last for almost three whole months. It should be noted that the more trendy blue colored Phalaenopsis found at many retailers aren’t naturally occurring. The blue is achieved by taking a white flowering orchid and injecting them with blue dye. Unfortunately, most of these orchids put through the treatment do not survive long, and those that do persist will bloom solid white. Phalaenopsis, like other orchids, are epiphytes, meaning they do not grow in soil or on the ground. Due to this they require a bark based, chunky potting mix that allows for adequate air flow to their specialized roots, which have been adapted to cling to the tree branches and rock formations where they are naturally found.

Cymbidium spp.

Boat Orchids

Growing wild in the Eastern hemisphere, tropical regions of Asia, the Himalayas, and all the way down to Australia, Cymbidium is another species that is quite popular. Their popularity started back in the Jin dynasty in China, with one of their first mentionings around 200 BC. Of all the orchids that Mrs. Mellon kept, these were the most plentiful. Understandably so, as these can be one of the larger sized plants, with almost every color, shape, and size bloom imaginable. Cymbidiums are considered semi-terrestrial and lend themselves well to greenhouse growing. One difference about growing cymbidiums is that they seem to prefer a temperature difference between day and night. Especially while they’re budding- its noted that they bloom best when temperatures drop to 46-50 degrees Fahrenheit at night, and temperatures can be brought back up again to 60-75 degrees once the buds open.

References:

Tomasi, Lucia Tongiorgi. An Oak Spring Flora: Flower Illustration from the Fifteenth Century to the Present Time: A Selection of the Rare Books, Manuscripts, and Works of Art in the Collection of Rachel Lambert Mellon. Yale University Press, 1997.