Coffee and Climate Change

OSGF

When Ellis discovered the fragrant and popular plant, he wrote an introduction to An Historical Account of Coffee describing the flower and fruit. While many of Ellis’ affiliated contemporaries studied plants, he was not only interested in growing them: he was most interested in the culture plants created. By the time he caught wind of Coffea arabica, it was most prominent as a beverage consumed while people assembled “in crowds to pass the time agreeably.” In 2017, we face the threat of losing the cultural staple to climate change.

From John Ellis' An Historical Account of Coffee.

John Ellis (c.1710-76) was a botanist and zoologist who wrote An Historical Account of Coffee, one of the first recorded western works that discusses the agricultural and economic beginnings of coffee. Published to promote the prosperity of Dominica, the book reflects the challenges of farming coffee: wages, trade, and colonization. Although its popularity peaked in the 18th century, An Historical Account of Coffee remains relevant today: farmers face the same economic challenges as the laborers in Ellis’ guide—now including the threat of climate change.

According to Ellis’ studies, the first encounter with coffee in the western world was recorded in an Arabian manuscript by Schehabeddin Ben, belonging to the king of France, which stated that coffee might have originated in Persia. Today we know that coffee was discovered in Kaffa, Ethiopia, given its proclivity for spontaneous growth. There is no other documentation on when, or how, coffee was consumed in this region, but those who first consumed it at large were aware of the effects of caffeine when they ate the coffee cherries or beans. Ben quotes the Musti of Aden’s observations of Persia’s coffee-drinking uses: “relieving the head-ach [sic], enlivening the spirits, and without prejudice to the constitution, preventing drowsiness.”

“For a century to come, it is perhaps more than probable, that the people of this country will, for one meal at least, make use of Tea, Coffee, or Chocolate..." —Dr. John Fothergill's letter

At the time of its discovery, Ellis was curious about coffee’s future influence on Europe, as coffee houses were to spread beyond the East and enter the everyday life of westerners. He includes in his book a letter from a merchant of London who writes on wages, proposed taxes, and the market value of the coffee bean. He wrote that “the revenue from the islands [producing coffee], arising from the 4½ per cent… must become so much more considerable” for planters to “fulfill their engagements.” In this way, the merchant recognized the economical effects on coffee producers—often foreign farmers.

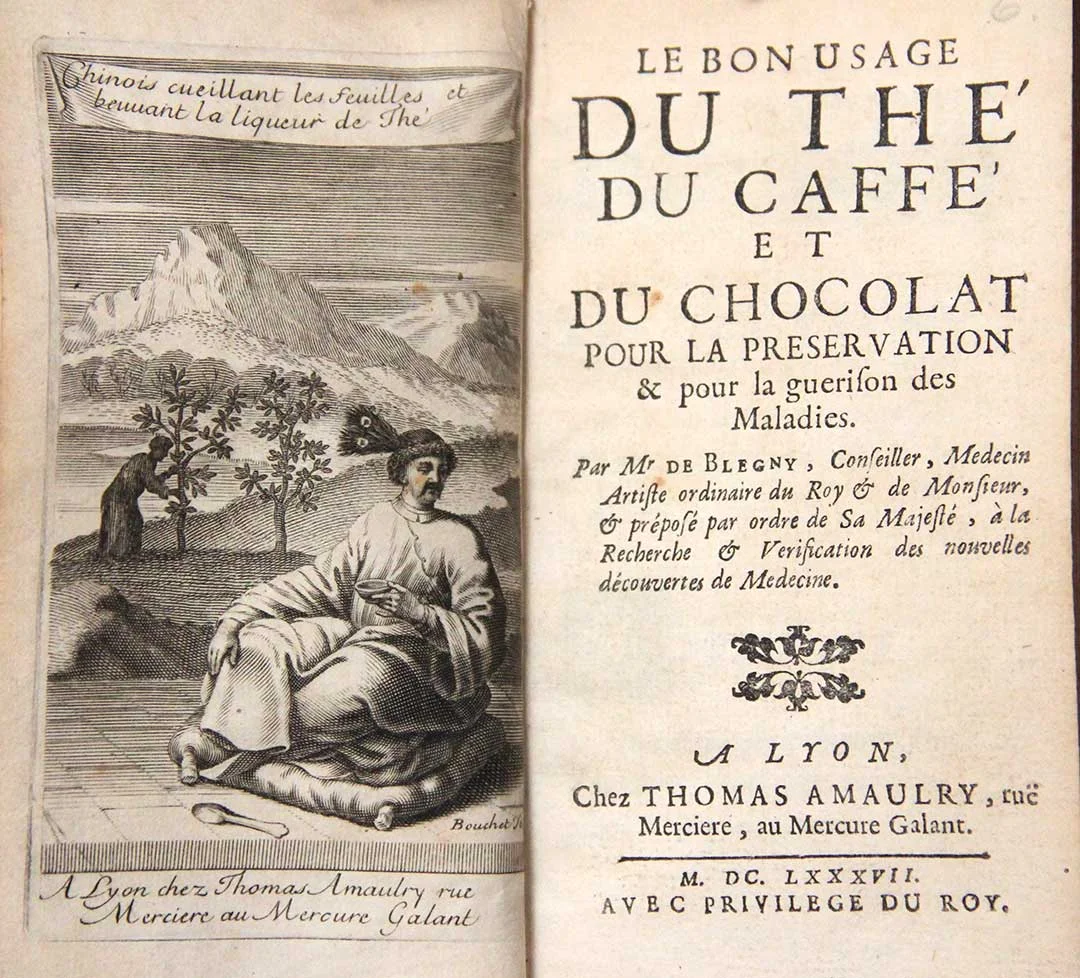

Nicolas de Blegny (1652-1722)

The merchant’s letter to Ellis also addressed trade with countries including Germany, of which he says: “Two years ago, the Germans readily gave double the price for coffee.” As the industry grew, the fluctuation of prices became a problem members of the government wished to influence. As it entered the western market, coffee was so desirable that European countries attempted to grow trees on their soil.

Dr. John Fothergill, a physician and plant collector, wrote to John Ellis regarding matters of where coffee was grown: “The greatest part of the Coffee made use in Europe is, I believe, the produce of the West Indies.” Enclosed in Ellis’ account of coffee, Fothergill’s letter records the concerns of western European nations, where soil was supposed to make coffee “assume another nature… not easily brought back to its original excellence.”

These countries still made attempts in their own climates, warranting criticism from Fothergill, who said the quality of soil should not deviate from that of Coffea arabica’s original home. Thus began the debate of “the culture of the plant, the curing of the fruit” all in the “highest perfection possible” in the west. Especially for physicians, the quality of coffee was just as important as the quantity—the plant’s health benefits required careful consideration as it became a cultural norm in Europe.

At the end of An Historical Account of Coffee, the merchant’s letter promotes free market trade and discourages Parliament from interfering with wages affecting coffee demand and yields. To the merchant, and to herbalists such as John Ellis, coffee was as much a matter of politics as it was a matter of culture and economics.

As ubiquitous as coffee is today, the modern industry faces the threat of climate change—Ethiopia, now the fifth largest producer of coffee in the world, faces the challenge of preparing for the rise in temperature this century. Ethiopia could lose up to 60% of its suitable farming land by the year 3000.

Differences in climatic variables by 2020 could make coffee production economically impractical for producers. Higher temperatures, long droughts punctuated by intense rainfall, more resilient pests, and plant diseases have resulted in damaged coffee yields in recent years. Based on a case study of Veracruz, Mexico, coffee production responds significantly to seasonal temperature patterns, particularly winter temperature, and changes in minimum wage. Climate change forecasts a dark future—one in motion today—for the cultural staple.

Today the greatest challenge of the earth’s inevitable rise in temperature means farmable land used for coffee plants will be reduced, and the coffee that can grow may ripen too quickly to develop the flavor and acidity that can create high-quality blends. As Fothergill suggested in his letter, “Let the coffee be planted in a soil as similar to its natural one as possible.”

While severe weather impacts coffee farmers in Ethiopia and Brazil, it seems that technology and innovation serves as the solution: with rampant deforestation in coffee-producing countries, more farming land has opened up, producing record yields. Coffee’s future relies heavily on the careful navigation of the world’s climate crisis, and how technology develops and governments adapt policy to prepare for temperatures rising.

As Dr. Carl Sagan once said, “You have to know the past to understand the present.” By using Ellis’ volume, we can see the changes coffee has been through, and how resilient it has been despite these economical and climatic variables. Ellis’ fascination with Coffea arabica led him to share historical knowledge that connected coffee to the challenges its producers would face.

Eventually Ellis would turn his research to the topic of coffeehouses becoming a hub for exchanging ideas in Europe. Interested in the globalization of plant life, he went on to publish volumes on the methodology of transporting plants overseas.