Dwellings of Possibilities

OSGF

Q&A With Kandis Phillips

Where have you been the past few months?

I have been at home in my suburban Maryland neighborhood since March fifth when the first case of human to human transmission of the Coronavirus was reported in our area. This voluntary isolation was at the recommendation of my Doctor who on March third told me, “If you get this virus it will probably kill you”. At first I considered the isolation to be a type of imprisonment. Later I came to realize the truth of an Emily Dickinson poem “I Dwell in Possibility” as I adjusted to my new reality within the confines of my home and small garden.

Historically, what ideas, issues, and subject matter(s) have inspired your work?

Historically my work has been inspired by poetry or literature, artifacts and the natural world. As a natural science illustrator I typically draw from museum specimens to document them for scientific research purposes. In my personal work I relate what I observe in nature through that lens in depicting accurately, yet often am influenced by poetic and historical means for inspiration and direction: Poetic through the work of Emily Dickinson; historic through the Renaissance technique of metalpoint drawing, and nature that is now limited to what I observe in my own backyard garden, specifically birds and their relationships to plants as witnessed in their nests.

What creative projects are you currently working on?

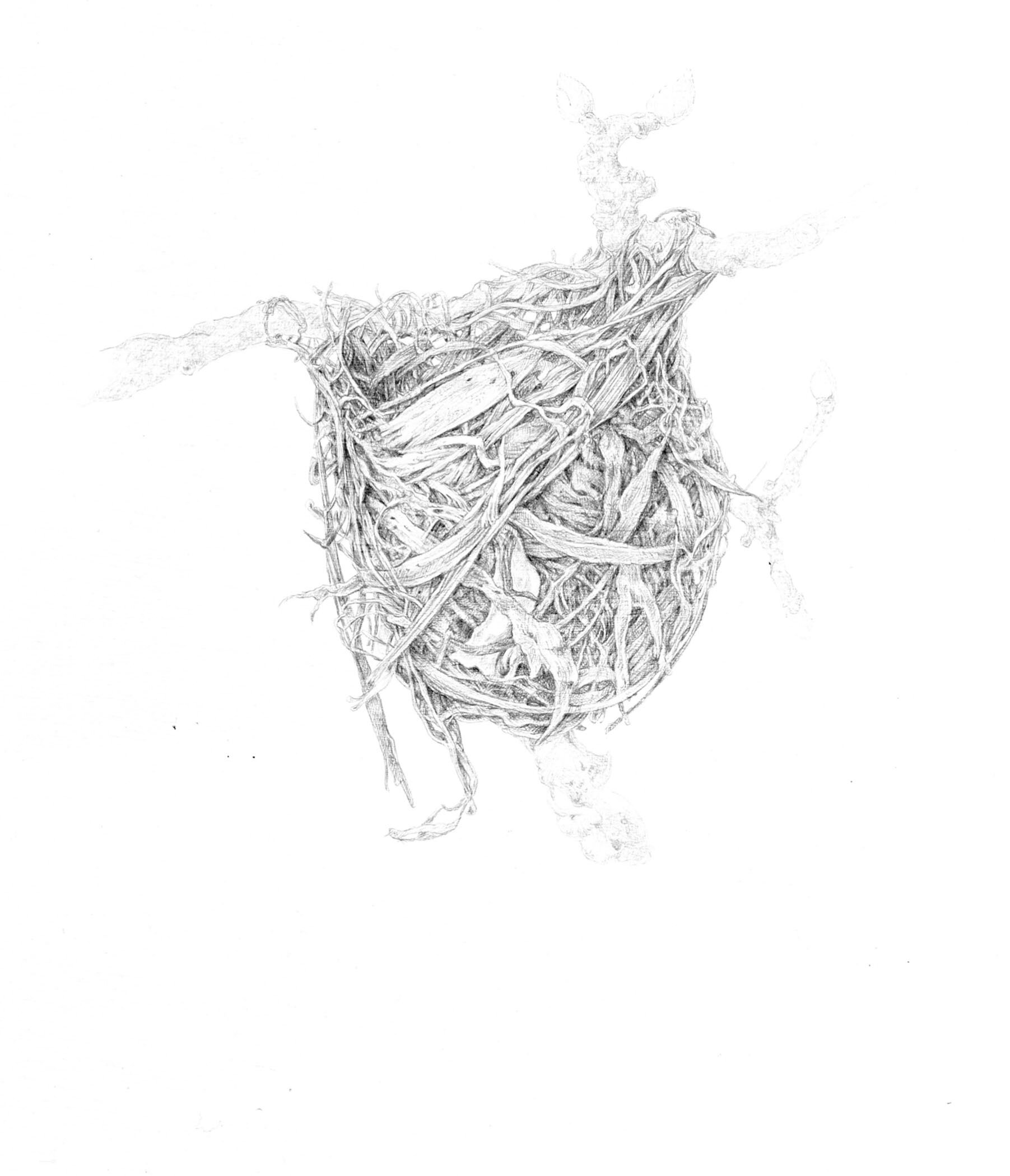

Currently I am working in a sketchbook journal depicting falconry and rehab birds from my photos and am including drawings of wings from my preliminary sketches and photos of museum specimens. I am also working on a series of metalpoint drawings of Abandoned Architecture, defined as bird nests left behind after their breeding season is completed. In this series I am drawing the nests I found recently while working on cleaning up the azalea hedges my yard. I took photos of the nests. According to the Migratory Bird Act, it is illegal to have bird nests in one’s possession, so I photograph them and leave them to the whims of nature.

How has your artistic practice changed during this time?

My artistic practice has changed in that I am broadening my scope; the dwelling in possibility aspect within the confines of my yard. With no access to my usual range of museum specimens, I am looking to what is available to me here and now. Pre-COVID I was working on an ongoing series of illustrating the plants found in Emily Dickinson’s herbarium, and in her poetry. Now I am focused on the plants, cultivated or weeds, growing in my yard and have pressed a number of spring ephemerals. I’ve taken a greater interest in the bird activity in my yard: opening a window at 4:45 am to listen to the dawn chorus; watching house finches strip a dandelion seed head; watching a house wren carefully select a blade of grass, carrying it to his nest box then cramming it in the small round entrance hole.

Has COVID-19 shifted how you think about the natural world?

The COVID-19 pandemic has made me think about the meaning of home, not just the usual time worn clichés, but the overall fragility of life. When cleaning out the azalea hedge from several years’ worth of accumulated trash and debris, a bird nest literally fell on my head. I began to think about the possibilities it held as a home for young, the possibility contained in the egg and the like. I marveled at its construction; its reliance on the fallen leaves, stems and grasses I was so busily trying to discard as yard waste but in reality were a treasure trove of building materials for birds. I thought of how many generations of catbirds- and I believed the nests to be catbird nests- had been raised in this hedge. I thought of how Museums hold an ark of materials available for scientists to probe the inner and outer workings of this earth; yet here under my azalea hedge there was also an ark and it was my responsibility to manage it properly. That means leaving the yard waste, leaving the dandelions and so forth.

Tell us about the work you submitted for this exhibit.

The nests drawings are all in metalpoint on various prepared papers. Metalpoint is a Renaissance drawing technique using actual metal, silver is the most common, and a paper coated with a ground such as gouache. The two Marsh Wren nests and the unknown nest (referred to as Abandoned Architecture Nest) are drawn from Museum specimens. They are artifacts, preserved and tied together with string and on display to educate the public. The two Vireo nests are actually the same nest but showing the front and back so to speak. I drove past this nest weekly and thought it was a small wasp nest. In January curiosity got the best of me and I went to investigate. It was about six feet up in a wild crabapple tree located halfway up a steep incline covered in honeysuckle vines and briers on the corner of a busy intersection. It is an extraordinary piece of craftsmanship, tightly woven from grasses and incorporating bits of plastic to imitate either a snakeskin or wasp paper as a deterrent to predators. The result was effective and certainly had fooled me. Think of the possibilities that that nest contained. All the nests are depicted life size and on pieces of paper ranging from 9x12 to 11x14.